"PASSEREA" Jarvis et al., 2014

Passerea, as defined by Jarvis et al. (2014), is not a clade in either Kuhl et al. (2021) or Stiller et al. (2024). The Jarvis et al. definition and descriptive comments make no sense if applied to either paper. Since I need a name for a clade including the Passeriformes, I've borrowed the name Passerea, redefining it to be compatible with the Stiller et al. topology. The quotation marks indicate the redefinition. Passerea was clearly intended to be the sister to what is called Columbaves in Stiller et al. This means that Otidimorphae (turacos, bustards, and cuckoos) is no longer part of "Passerea". Otherwise, it is unchanged. The next branch in Neoaves is Elementaves. It's sister clade is called Telluraves, so the new "Passerea" is Elementaves + Telluraves. All three clades seem to have originated very close to the K-Pg boundary, about 66 mya.

ELEMENTAVES Stiller et al., 2024

GRUAE Bonaparte, 1854

This page is titled Gruae because an earlier analysis (Jarvis et al., 2014) indicated that the Opisthocomiformes (Hoatzin), Gruiformes (Cranes, Rails, etc.) and Charadriiformes (Shorebirds) form a clade. Jarvis et al. found that bootstrap support for this clade was 91%. Support for Gruimorphae (Gruiformes plus Charadriiformes) was even higher (96%). Suh et al. (2015) also obtained the same clade. More recently, Kuhl et al. (2020) found Gruimorphae, but not Gruae, but the OpenWings project did find Gruae in its 2019 supertree. More to the point, so did Stiller et al. (2024).

Some analyses have disagreed. Prum et al. (2015) put each component of Gruae in a different place, as did Braun and Kimball (2021). In fact, one of Jarvis et al.'s alternative trees had the Hoatzin on its own branch, rather than part of Gruae.

Stiller et al. (2024) used massively more data than any of the other papers. Moreover, they appear to have found the source of the apparent polytomy and corrected for it. One consequence is that the Hoatzin problem has finally been solved! The Hoatzins are the sister group to Gruimorphae, the clade consisting of Gruiformes (cranes and rails) and Charadriiformes (shorebirds).

OPISTHOCOMIMORPHAE Swainson, 1837

The Opisthocomimorphae contain a single extant species, the Hoatzin, and are restricted to South America (mainly in the Amazon and Orinoco basins). This was not always true. There is fossil evidence of Opisthocomiformes from both Africa and Europe. More specifically, there are fossils from Namibia (Mayr, Alvarenga, and Mourer-Chauviré, 2011), Kenya (Mayr, 2014c), and France (Mayr and De Pietri, 2014), as well as from South America. There is also a fossil from the Green River Formation in Wyoming that has some similarities to Opisthocomimorphae (Olson, 1992), but its true affinites are unknown and could be related to cuckoos or turacos. The origins of the Opisthocomimorphae date to near the K-Pg boundary, roughly 66 mya according to Stiller et al. (2024).

OPISTHOCOMIFORMES L'Herminier, 1837

A morphological analysis of modern Opisthocomus, and fossil Hoazinavis (Brazil, 22-24 mya), Protoazin (France, 34 mya), and Namibiavis (Namibia and Kenya, 15-17.5 mya), found Hoazinavis most closely related to modern Opisthocomus, followed by Protoazin, with Namibiavis the most distant relative.

A long list of living bird families have been considered the closet relatives of the Hoatzin, including seriemas, cuckoos, turacos, rails, doves, and others. The lack of any close relatives justifies placing it in its own superorder. Fain and Houde (2004) and Ericson et al. considered it part of Metaves. The TiF list currently follows Jarvis et al. (2014), who put it as the basal taxon in Gruae. However, the bootstrap support is only 91%, so there is uncertainty about this. The Hoatzin could belong to one of the other high level groups, or even form its own high level group (Jarvis et al, 2014, Fig. 3b).

Opisthocomidae: Hoatzin Swainson, 1837

1 genus, 1 species HBW-3

- Hoatzin, Opisthocomus hoazin

GRUIMORPHAE Bonaparte, 1854

Gruimorphae consists of two groups: Gruiformes and Charadriiformes. Their most recent common ancestor seems to have lived about 65 mya, see Stiller et al. (2024). The Gruiformes are covered on this page. Click here for the Charadriiformes.

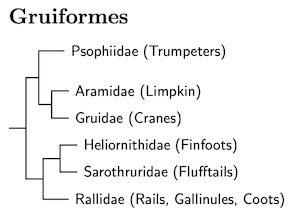

GRUIFORMES Bonaparte, 1854

|

| Gruiform Family Tree |

|---|

All sorts of taxa have been previously been included in the Gruiformes, which formerly seemed to serve as a waste-bin taxon. The mesites, kagu, and sunbittern were once considered Gruiformes. This version of the Gruiformes is a more coherent clade. The family order is based on Fain et al. (2007) and Hackett et al. (2008) for the separation of the Sarothruridae. Mayr (2008a) discusses both DNA and morphological support for this clade (without Sarothruridae). This arrangement is still current in 2021.

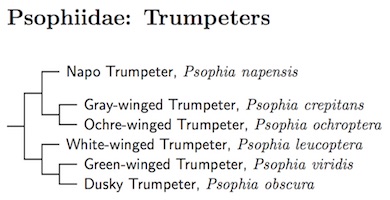

Psophiidae: Trumpeters Mathews, 1913

1 genus, 6 species HBW-3

The trumpeters are an ancient lineage, probably becoming distinct from the limpkins and cranes in the Paleocene or Eocene. Nonetheless, the current crop of trumpeters are quite closely related. Indeed, Ribas et al. (2012) estimate that the common ancestor of all the extant trumpeters lived about 3 million years ago. At some point within the last few million years, only one trumpeter species left present-day descendants. Since the trumpeters have been around roughly 50 million years, it is likely that many species of trumpeters died out. This suggests that extinction plays a very important role in the biodiversity that we see, and that it hides much avian history.

Although the SACC arranges the 8 recognized subspecies of trumpeter into 3 species, I currently recognize 6 species. Oppenheimer and Silveira (2009) suggest that interjecta is indistinguishable from dextralis. Ribas et al. (2012) found 8 genetically distinct lineages, including interjecta. However, the genetic distance between interjecta and dextralis was small. The subspecies obscura was slightly more distinct, having separated roughly 500,000 years ago. The case for treating these as separate species is weak. For now I group them all as P. obscura. The other races of trumpeter are more distinct from one another, having likely separated from nearly 1 to about 2 million years ago. In the case of napensis and ochroptera, there is no sign of interbreeding in spite of a range overlap. This suggests they are separate species, and provides support for treating the remaining trumpeters as separate species.

Ribas et al. (2012) also show how the separation of the trumpeters relates to the formation of various riverine barriers in the Amazon region. The various trumpeters inhabit several of the well-known areas of endemism in the Amazon. If other types of animal show a similar pattern and timing of separation, it will help explain the existence of these areas of endemism.

The additional English names are those used by Hellmayr and Conover (1942), sometimes for subspecies.

- Napo Trumpeter, Psophia napensis

- Gray-winged Trumpeter, Psophia crepitans

- Ochre-winged Trumpeter, Psophia ochroptera

- White-winged Trumpeter, Psophia leucoptera

- Green-winged Trumpeter, Psophia viridis

- Dusky Trumpeter, Psophia obscura

Aramidae: Limpkin Bonaparte, 1842

1 genus, 1 species HBW-3

- Limpkin, Aramus guarauna

Gruidae: Cranes Vigors, 1825

4 genera, 15 species HBW-3

The basic structure of the crane family has been known for some time. I follow H&M-4 concerning crane genera, which divides the cranes into four genera and recognizes the deep division between the crowned cranes and the rest by putting the genus Balearica in its own subfamily. Some authors further divide the cranes, but not all of these divisions fit the genetic data. This was already visible in the DNA hybridization analysis of Krajewski (1989). It was even clearer in the cytochrome-b analysis of Krajewski and Fetzner (1994). Fain, Krajewski, and Houde (2007) refine this in a multi-gene analysis. The most recent analysis is that of Krajewski et al. (2010). They use the complete mitochondrial genome, and their analysis is followed here.

The Wattled Crane, formerly Grus carunculatus, has been moved to genus Bugeranus (Gloger 1842). This is because it is a distinctive species, compared with its closest relatives (Anthropoides) and it their common ancestor seems to have lived about 7 mya (Krajewski et al., 2010). Together with the Demoiselle and Blue Cranes, they form a clade that split from the other clades roughly 11 mya, so they get a new genus too, the aforementioned Anthropoides (Vieillot 1816, type virgo). Thus they are Demoiselle Crane, Anthropoides virgo and Blue Crane, Anthropoides paradiseus.

Balearicinae: Crowned Cranes Brasil, 1913

- Gray Crowned-Crane, Balearica regulorum

Click for Gruidae tree - Black Crowned-Crane, Balearica pavonina

Gruinae: Cranes Vigors, 1825

- Siberian Crane, Leucogeranus leucogeranus

- Sandhill Crane, Antigone canadensis

- White-naped Crane, Antigone vipio

- Sarus Crane, Antigone antigone

- Brolga, Antigone rubicunda

- Wattled Crane, Bugeranus carunculatus

- Demoiselle Crane, Anthropoides virgo

- Blue Crane, Anthropoides paradiseus

- Red-crowned Crane, Grus japonensis

- Whooping Crane, Grus americana

- Common Crane, Grus grus

- Hooded Crane, Grus monacha

- Black-necked Crane, Grus nigricollis

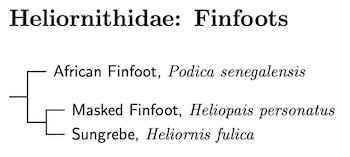

Heliornithidae: Finfoots G.R. Gray, 1840

3 genera, 3 species HBW-3

|

| Heliornithidae (Finfoot) tree |

|---|

- African Finfoot, Podica senegalensis

- Masked Finfoot, Heliopais personatus

- Sungrebe, Heliornis fulica

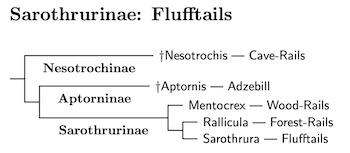

Sarothruridae: Flufftails

|

| Sarothruridae (Flufftail) tree |

|---|

There have been suggestions that this group deserves recognition as a family since at least Sibley and Ahlquist (1985). Hackett et al. (2008) found that Sarothrura is more closely related to the finfoots than to the rails. Garcia-R. et al. (2014a) found that same is true of Canirallus, and that it is more closely related to Sarothrura than to the finfoots. Accordingly, they are placed in a separate family.

Canirallus / Mentocrex Split: The genus Canirallus has been split as it was found that part of the genus belonged to the Sarothruridae, and part to the Raillidae. See Boast et al. (2019), Kirchman et al. (2021), and Oswald et al. (2021). According, one species is retained in Canirallus, the Gray-throated Rail, Canirallus oculeus. The other two move to Mentocrex (JL Peters 1932), type kioloides. Canirallus moves back to the Rallidae, while Mentocrex remains in Sarothruridae.

The Tsingy Wood Rail, Mentocrex beankaensis, has been newly discovered within the Madagascan Wood Rail complex. See Goodman et al. (2011).

Livezey (1998) suggested that Rallicula (formerly part of Rallina) may also belong with the flufftails based on a phylogenetic analysis of osteological, myological, and integumentary characters.

Finally, recently discovered ancient DNA evidence indicates that both the extinct cave-rails of the Caribbean (Nesotrochis) and the extinct adzebills of New Zealand (Aptornis) are in the flufftail clade. Given their ancientness, I've ranked them both as subfamilies in Sarothruridae. See Oswald et al. (2021) and Boast et al. (2019). Although these lineages are ancient, the final extinctions happened fairly recently.

3 genera, 15 species Not HBW Family

- Madagascan Wood Rail, Mentocrex kioloides

- Tsingy Wood Rail, Mentocrex beankaensis

- Chestnut Forest-Rail, Rallicula rubra

- White-striped Forest-Rail, Rallicula leucospila

- Forbes's Forest-Rail, Rallicula forbesi

- Mayr's Forest-Rail, Rallicula mayri

- White-spotted Flufftail, Sarothrura pulchra

- Buff-spotted Flufftail, Sarothrura elegans

- Red-chested Flufftail, Sarothrura rufa

- White-winged Flufftail, Sarothrura ayresi

- Slender-billed Flufftail, Sarothrura watersi

- Streaky-breasted Flufftail, Sarothrura boehmi

- Chestnut-headed Flufftail, Sarothrura lugens

- Striped Flufftail, Sarothrura affinis

- Madagascan Flufftail, Sarothrura insularis

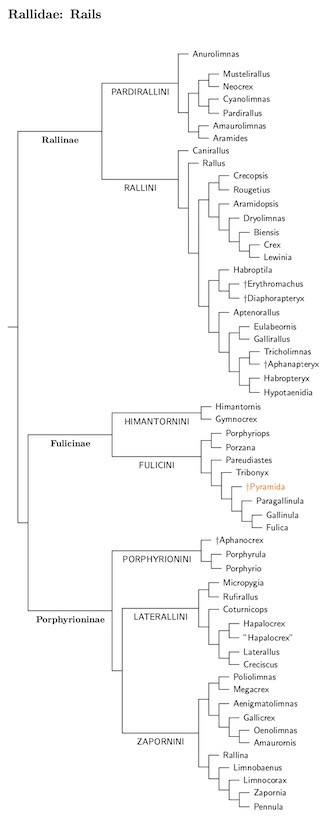

Rallidae: Rails, Gallinules, Coots Rafinesque, 1815

56 genera, 152 species HBW-3

|

| Click for Rallidae species tree |

|---|

As I write, the most comprehensive published phylogeny of the rails is Garcia-R. and Matzke (2021). The papers by Kirchman et al. (2021) and Boast et al. (2019) are also quite helpful. Garcia-R. and Matzke (2021) combine molecular data with morphological data from Livezey (1998) to provide a nearly complete phylogeny of the rails.

However, that is not quite what I'm using for TiF. There are a number of species where DNA was available, but not used by Garcia-R. and Matzke. In fact, some of that DNA is even from another Garcia-R. paper (Garcia-R. and Trewick, 2015). There are other examples of unused DNA, and I've modified the Garcia-R./Matzke phylogeny in an attempt to incorporate this extra DNA data. This is made considerably easier by the fact that some of the extra taxa involve entire clades. In particular, Maley and Brumfield (2013) studied the Clapper/King Rail clade; Garcia-R. and Trewick (2015) examined the swamphens; Groenenberg et al. (2008) focused on the moorhens and Slikas et al. (2002) focused on a clade in the Zapornini (their clade 3). In these cases, I just pulled out the version of each clade from the Garcia-R. and Matzke phylogeny and dropped in a replacement.

Other additional DNA involved an isolated species or species pair, and was a little more difficult to weave in. In some of these cases it was impossible to get a consensus. For this, I consulted the papers by Trewick (1997), Kirchman (2012), Boast et al. (2019), Stervander et al. (2019), Chaves et al. (2020), Garcia-R. et al. (2020), and Kirchman et al. (2021). Besides published papers, I also used the 2014 reanalysis of archived data by Raty on BirdForum, for the Speckled Rail, Creciscus notatus.

To help see what DNA was used,, I've added some special markings to the species tree. If Garcia-R. and Matzke used DNA, the species name has a trailing black asterisk. Species where I only had other DNA available have a trailing red asterisk. Species in orange indicate extinct species that are not currently on the TiF list. Some of them have “ancient” DNA available, in which case they have a trailing asterisk. There are other annotations on the tree, so I've included a key at the end of the tree.

Needless to say, the new phylogeny has involved some big changes. The basic structure still involves three subfamilies: Rallinae (which is basal), and the sister subfamilies Fulicinae (has priority over the previously used Gallinulinae) and Porphyrioninae. But the composition of these has changed somewhat.

Rallinae now contains two tribes, Pardirallini (moved from Fulicinae) and Rallini. Fulicinae is also split into two tribes, the new tribe Himantornithini and the old Fulicinini (previously called Gallinulini). The last subfamily, Porphyrioninae now has three tribes: Porphyrionini (basal) followed by Laterallini and Zapornini.

The most noticeable changes involve the genera, which have ballooned from 43 to 56! One driving force behind this is that Garcia-R. and Matzke (2021) provide time estimates for every branch in the supplementary material, which is useful when trying to decide whether a separate genus is needed.

So how old is the rail family? Garcia-R. and Matzke (2021) don't address this, but Garcia-R. et al. (2014) did. They put the split between the rails and flufftail/finfoot clade at about 61 mya ±9 million years. The high side of that range is probably too high as it is on the other side of the KT boundary. Others have also tried to address this question. Figure 4 in Kirchman et al. (2021) puts it about 40 mya, with a range of roughly 32-53 mya. In Boast et al. (2019, Figure 2) it's at 54 mya, with a range of about 41-70 mya. As you can see, these estimates are not very precise!

The three subfamilies date to 25-30 mya according to Garcia-R. and Matzke, or 10 million older according to Boast et al. (2019), while Kirchman et al. (2021) prefer a date in-between those two. Again, we have no precise number, but the relative scales are still helpful in deciding which clades should be subfamilies.

Canirallus returns: Before considering the subfamilies, we first return one species to the Rallidae. The genus Canirallus, previously placed in Sarothruridae, has been split. Boast et al. (2019), Kirchman et al. (2021), and Oswald et al. (2021) found that part was in Rallidae (Canirallus), and the other part (Mentocrax) in Sarothruridae. As a result, Canirallus now consists of a single species, the Gray-throated Rail, Canirallus oculeus.

Rallinae: Long-billed Rails and allies Rafinesque, 1815

There is single deep division in Rallinae, that is about 24.4 million years old according to Garcia-R. and Matzke (2021). It divides the Rallinae into two tribes: Pardirallini and Rallini. There are also some lesser divisions within Rallini, with clades, involving Rallus, Crex, and Gallirallus. However, those are enough more recent than the tribal divisions (16.5-18.5 mya) that I do not rank them as tribes (and TiF is allergic to subtribes).

The Canirallus problem: However, I've glossed over a problem. Canirallus has been reduced to a single species, the Gray-throated Rail, Canirallus oculeus. We need to ask, where does it go? There are three relevant papers: Boast et al. (2019), Kirchman et al. (2021), and Oswald et al. (2021). Oswald et al. make clear that Canirallus belongs in Rallinae, and is a fairly basal branch, possibly the basal branch. However, they don't include any members of Pardirallini, so we can't say much more. Kirchman et al. (2021, Taxon Set C) put it in Rallini. Boast et al. (2019, Fig. 3) put it in Pardirallini. In other words, there's a complete lack of consensus.

Can morphology help? Livezey (1998) says Canirallus is in “a poorly resolved set of rallid genera”, which is not helpful. However, his tree suggests it is more likely in the Rallini. Since Pardirallini is confined to the Americas and Canirallus is African, this makes sense (but I could tell a story the other way too). Moreover, the plumage seems more in line with Rallini that Pardirallini. In the end, I'm placing it in Rallini as the basal branch, but my confidence in this at best medium. With that out of the way, we can now consider the two tribes of Rallinae.

Pardirallini

Compared with the previous treatment in TiF, I've moved the Pardirallini to subfamily Rallinae where they join the Chestnut-headed Crake, Anurolimnas castaneiceps. Otherwise, the composition is unchanged, but has been rearranged a little.

Genus Changes: There are some changes of genus:

- The Colombian Crake, Mustelirallus colombiana and Paint-billed Crake, Mustelirallus erythrops are transferred to genus Neocrex (Sclater and Salvin, 1869), type erythrops.

- The Zapata Rail, Mustelirallus cerverai returns to the monotypic genus Cyanolimnas (Barbour and JL Peters, 1927).

Wood-Rails: Based on Marcondes and Silveira (2015), the Russet-naped Wood-Rail, Aramides albiventris, including subspecies mexicanus, vanrossemi, pacificus, and plumbeicollis, has been split from Gray-necked Wood-Rail, Aramides cajaneus. Both the AOS NACC and SACC have also changed the name of Gray-necked Wood-Rail to Gray-cowled Wood-Rail.

The phylogeny in Garcia-R. and Matzke (2021) suggests that mexicana and plumbeicollis are better regarded as subspecies of the Rufous-necked Wood-Rail, Aramides axillaris rather than the Russet-naped Wood-Rail, Aramides albiventris. If this was based on DNA, I would have to take it seriously. However, this is based purely on morphology and the calls of the birds disagree. The sound like albiventris. If you have any doubts, consult SACC #797. If you still have doubts, listen to the songs on Xeno-canto.org.

Rallini

As mentioned above, Rallini loses two species to Pardirallini. It also loses the three Gymnocrex species to Himantornithini, but gains Gray-throated Rail, Canirallus oculeus, from Sarathruridae and Rouget's Rail, Rougetius rougetii, previously considered incertae sedis.

Virginia Rail: There is one more addition to Rallini — a split. Based on Ridgely and Greenfield (2001) and the fact that the birds in Ecuador sound quite different from those in North America, the Virginia Rail, Rallus limicola, is split into:

- Virginia Rail, Rallus limicola

- Ecuadorian Rail, Rallus aequatorialis, including meyerdeschauenseei

Clapper and King Rails: We also have an older split that's been in TiF for a while. Based on Maley (2012) and Maley and Brumfield (2013), King Rail, Rallus elegans, has been split into:

- King Rail, Rallus elegans (eastern North America, Cuba) and

- Aztec Rail, Rallus tenuirostris (central Mexico).

Further, Clapper Rail, Rallus longirostris, has been split into:

- Clapper Rail, Rallus crepitans, (Caribbean and eastern North America)

- Ridgway's Rail, Rallus obsoletus, (western North America), and

- Mangrove Rail, Rallus longirostris, (South America).

The table below puts them in their proper order and list the subspecies and describes the ranges.

| Clapper/King Rail complex | ||

|---|---|---|

| Species | Subspecies | Range |

| Ridgway's Rail R. obsoletus |

obsoletus, levipes, yumanensis, rhizophorae, beldingi |

western US, western Mexico |

| Aztec Rail R. tenuirostris |

tenuirostris | central Mexico |

| Mangrove Rail R. longirostris |

phelpsi, margaritae*, pelodramus*, longirostris*, crassirostris*, cypereti |

South America |

| King Rail R. elegans |

elegans, ramsdeni | eastern US and Mexico, Cuba |

| Clapper Rail R. crepitans |

crepitans, saturatus, waynei, scottii, insularum, pallidus*, grossi*, belizensis*, coryi, leucophaeus, caribaeus |

eastern US and Mexico, Belize, Caribbean |

| * = subspecies not sampled by Maley and Brumfield (2013). | ||

Mangrove(?) Rails have recently been discovered along the Pacific Coast of southern Central America (esp. the Gulfs of Fonseca and Nicoya). There is also a report from the Atlantic coast (Panama: Bocos del Toro). I do not know if any have definitely identified as to subspecies, but Van Dort (2013) suggests the Pacific coast rails are Mangrove Rails. In any event, they currently seem to be accepted as Mangrove Rails.

Genus Changes: As of version 3.07 of this page, TiF recognizes a number of new genera in Rallini.

- The African Crake, Crex egregia, is not sister to the Corn Crake, so it moves to the monotypic genus Crecopsis (Sharpe, 1893).

- The Snoring Rail, Lewinia plateni has moved away from Lewinia to become the monotypic genus Aramidopsis (Sharpe, 1893).

- The Red Rail, Aphanapteryx bonasia and Rodrigues Rail, Erythromachus leguati will move into the Gallirallus group, which is spilt up into various genera, many of them monotypic.

- The Invisible Rail, Gallirallus wallacii is now in the monotypic genus Habroptila (Gray, 1861).

- Hawkins's Rail, Gallirallus hawkinsi has become the monotypic genus Diaphorapteryx (Forbes, 1892).

- The Calayan Rail, Gallirallus calayanensis becomes genus Aptenorallus (Kirchman et al., 2021).

- The Chestnut Rail, Gallirallus castaneoventris becomes genus Eulabeornis (Gould, 1844).

- The New Caledonian Rail, Gallirallus lafresnayanus becomes Tricholimnas (Sharpe, 1893).

- The Chatham Rail, Gallirallus modestus joins Aphanapteryx (Frauenfeld, 1868), type bonasia.

- The Okinawa Rail, Gallirallus okinawae, Barred Rail, Gallirallus torquatus, and Pink-legged Rail, Gallirallus insignis are all moved to Habropteryx (Stresemann, 1932), type insignis.

- Finally, the rest of Gallirallus is transferred to genus Hypotaenidia (Reichenbach, 1853), type philippensis.

Woodford's Rail Complex: While studying Garcia-R and Matzke (2021) and related papers, I noticed a small problem concerning the Woodford's Rail complex in the Garcia-R and Matzke phylogeny. So let's consider Woodford's Rail, Hypotaenidia woodfordi. Like IOC, TiF treats as a single species with three subspecies: woodfordi, immaculata and tertia. In contrast, HBW elevates the subspecies to full species status yielding

- Bougainville Rail, Hypotaenidia tertia

- Santa Isabel Rail, Hypotaenidia immaculata

- Guadalcanal Rail, Hypotaenidia woodfordi

Garcia-R. and Matzke seem to follow this too, but use Gallirallus rather than Hypotaenidia. In any event, both G. woodfordi and G. immaculatus appear on their tree.

So what's the problem? Garcia-R et al. (2014a) had previously sampled DNA from a specimen at the Burke Museum in Seattle, with the results submitted to GenBank in 2013 as Nesoclopeus woodfordi. It is also referred to that way in the nex files for Garcia-R. and Matzke (2021). It wasn't noted originally that the DNA sample was actually immaculatus, from Isabel, Solomon Islands. It was just listed as woodfordi from the Solomons. This is clear in the supplementary data for the 2014a paper. In fact, the very same specimen together with another at the Burke was previously sampled by Kirchman (2009), who correctly listed them as immaculatus from Isabel, Solomon Islands.

So what this means is that for Garcia-R and Matzke, G. immaculatus has the means morphological characteristics of immaculatus, but no DNA, and their G. woodfordi is an odd type of chimera, with the morphological characteristics of G. woodfordi but DNA of G. immaculatus. Opps!

Since woodfordi seems to be in roughly the right place, genetically speaking, this has an easy fix. I put Woodford's Rail (including the subspecies) where G. woodfordi was, and supressed G. immaculatus as an error.

There's some question about how old the branches are in the clade containing Hypotaenidia. Kirchman (2012) argued that many of them are very young, but Garcia-R. and Matzke (2021) gave much older ages that would suggest using even more genera than I have used. I have compromised here, and consider that the current Hypotaenidia makes a reasonably coherent group.

Kirchman argued that the genetic distances between all the Gallirallus species is fairly small, and indicates a common ancestry as recently as a million or so years ago. This is amazingly recent!

I don't believe this. In particular, I think he has chosen a calibration point unwisely. He based the ages on the fact that rails cannot have been on Wake Island for more than about 125,000 years. The idea is that Wake Island was completely submerged at that time. When he applied more conventional molecular dating he obtained a much older date, about 7.8 million years ago, suggesting that the Wake Island Rail recently arrived from another island. This suggests a very rapid loss of the ability to fly. Kirchman (2012) found that the extinct Wake Island Rail's closest relative was the extinct Mangaia Rail, Gallirallus ripleyi from the Cook Islands. The Mangiaia Rail is known only from subfossil remains that appear to be 700-1000 years old, and its date of extinction is uncertain. It is not included on the main list, but is included in the Rallidae tree.

Interestingly, Garcia-R. and Matzke (2021) give a different topology for this clade and an age of approximately 1.5 million years for split between the Wake Island Rail, Hypotaenidia wakensis, and the Guam Rail, Hypotaenidia owstoni (which is not its closest relative).

The extinct Sharpe's Rail, Gallirallus sharpei, is known from one specimen from an unknown location. Kirchman (2012) did not obtain DNA from Sharpe's Rail. According to Bird Life International, it is now thought to have been a color morph of Buff-banded Rail, Gallirallus philippensis. I've not seen any published information on this.

Pardirallini: Wood-Rails and allies Livezey, 1998

- Chestnut-headed Crake, Anurolimnas castaneiceps

- Ash-throated Crake, Mustelirallus albicollis

- Paint-billed Crake, Neocrex erythrops

- Colombian Crake, Neocrex colombiana

- Zapata Rail, Cyanolimnas cerverai

- Plumbeous Rail, Pardirallus sanguinolentus

- Spotted Rail, Pardirallus maculatus

- Blackish Rail, Pardirallus nigricans

- Uniform Crake, Amaurolimnas concolor

- Little Wood-Rail, Aramides mangle

- Rufous-necked Wood-Rail, Aramides axillaris

- Russet-naped Wood-Rail, Aramides albiventris

- Giant Wood-Rail, Aramides ypecaha

- Gray-cowled Wood-Rail, Aramides cajaneus

- Brown Wood-Rail, Aramides wolfi

- Red-winged Wood-Rail, Aramides calopterus

- Slaty-breasted Wood-Rail, Aramides saracura

Rallini: Long-billed Rails and allies Rafinesque, 1815

- Gray-throated Rail, Canirallus oculeus

- Plain-flanked Rail, Rallus wetmorei

- Ridgway's Rail, Rallus obsoletus

- Aztec Rail, Rallus tenuirostris

- Mangrove Rail, Rallus longirostris

- King Rail, Rallus elegans

- Clapper Rail, Rallus crepitans

- Water Rail, Rallus aquaticus

- Brown-cheeked Rail, Rallus indicus

- African Rail, Rallus caerulescens

- Virginia Rail, Rallus limicola

- Ecuadorian Rail, Rallus aequatorialis

- Bogota Rail, Rallus semiplumbeus

- Austral Rail, Rallus antarcticus

- African Crake, Crecopsis egregia

- Rouget's Rail, Rougetius rougetii

- Snoring Rail, Aramidopsis plateni

- White-throated Rail, Dryolimnas cuvieri

- †Reunion Rail, Dryolimnas augusti

- Madagascan Rail, Biensis madagascariensis

- Corn Crake, Crex crex

- Slaty-breasted Rail, Lewinia striata

- Brown-banded Rail, Lewinia mirifica

- Lewin's Rail, Lewinia pectoralis

- Auckland Rail, Lewinia muelleri

- Invisible Rail, Habroptila wallacii

- †Rodrigues Rail, Erythromachus leguati

- †Hawkins's Rail, Diaphorapteryx hawkinsi

- Calayan Rail, Aptenorallus calayanensis

- Chestnut Rail, Eulabeornis castaneoventris

- Weka, Gallirallus australis

- New Caledonian Rail, Tricholimnas lafresnayanus

- †Red Rail, Aphanapteryx bonasia

- †Chatham Rail, Aphanapteryx modesta

- Pink-legged Rail, Habropteryx insignis

- Okinawa Rail, Habropteryx okinawae

- Barred Rail, Habropteryx torquatus

- Lord Howe Woodhen, Hypotaenidia sylvestris

- Woodford's Rail, Hypotaenidia woodfordi

- †Bar-winged Rail, Hypotaenidia poeciloptera

- †Dieffenbach's Rail, Hypotaenidia dieffenbachii

- Buff-banded Rail, Hypotaenidia philippensis

- Roviana Rail, Hypotaenidia rovianae

- Guam Rail, Hypotaenidia owstoni

- †Tahiti Rail, Hypotaenidia pacificus

- †Wake Island Rail, Hypotaenidia wakensis

Fulicinae Nitzsch 1829

The next group is the Fulicinae. Obviously, it contains the coots (Fulica). It's split into two tribes: Himantornithini and Fulicini. Although the coots and moorhens are here, neither the swamphens nor the American Purple Gallinule are part of the Fulicinae.

Himantornithini

Himantornithini contains two genera: Himantornis and Gymnocrex. Kirchman et al. (2021) is the only paper to include DNA from both genera. They found them to be sister genera. Garcia-R. and Matzke found the same thing, basing their conclusion on morphology rather than DNA. Unlike Garcia-R. and Matzke (2021), both Garcia-R. et al. (2020) and Kirchman et al. found Himantornis sister to Fulicini, and that is how I will treat them. This group is a distant sister of Fulicini, so I've placed them in separate tribes. Since the topology is different from that in Garcia-R. and Matzke, we can't get a read on the distance. However, Kirchman et al. found them intermediate in age between the Porphyrionini branch and the Laterallini/Zapornini split. Translated to the Garcia-R. and Matzke paper, that would be an age of 26 to 28.5 million years.

So why do Garcia-R. and Matzke (2021) put Himantornithini sister to the rest of the Rallidae? I don't know, perhaps the morphological data they use, combined with limited DNA causes it. Certainly, their positionning of Himantornithini is much the same as Liverzey (1998), based purely on morphological data. We know that weird things can happen when using morphological data. Garcia-R. and Matzke unintentionally demonstrate this with the Nesotrochis cave-rails. They place the cave-rails next to the Aramides wood-rails. In fact, there is genetic data for the cave-rails (Oswald et al., 2021). They found the cave-rails belong to the Flufftail family, Sarothruridae.

Fulicini

Fulicini mainly contains the moorhens/gallinules and coots, together with the similar woodhens and native-hens. Fulicini also contains the remaining portion of Porzana, after many species have been transferred to Zapornia and elsewhere. I follow Christidis and Boles (2008) and separate Pareudiastes (Hartlaub and Finsch, 1871), type pacificus, and Tribonyx (DuBus, 1840), type mortierii, from Gallinula.

Spot-flanked Gallinule: The Spot-flanked Gallinule, formerly in Gallinula, is now in the monotypic genus Porphyriops (Pucheran 1845). Raty's reanalysis found that the Spot-flanked Gallinule, Porphyriops melanops, belongs near Porzana. This makes sense as the Spot-flanked Gallinule looks much like a Sora, Porzana carolina. Garcia-R. et al. (2014), using more data, placed it as shown on the diagram and estimated that the common ancestor of Porzana and Porphyriops lived perhaps 20 million years ago. I believe this number to be somewhat exaggerated, perhaps by 40%. Even so, they would still be separated by 12 million years, more than enough to put them in different genera. The placement sister to Porzana is supported by Boast et al. (2019), Garcia-R. et al. (2020), and Kirchman et al. (2021), using partially different gene sets, although Garcia-R. and Matzke (2021) put it in a different position.

Lesser Moorhen: The Lesser Moorhen is now Paragallinula angulata instead of Gallinula (Sangster, Garcia-R., and Trewick, 2015), type angulata. This change was needed because Paragallinula is basal to both Gallinula (true gallinules and moorhens) and Fulica (coots).

Common Gallinule/Moorhen: This list treats the Common Gallinule, Gallinula galeata and Common Moorhen, Gallinula chloropus, as separate species, as does the AOU (both NACC and SACC). Groenenberg et al. (2008) found that the Common Moorhen is more closely related to the Gough Moorhen, Gallinula comeri, and the extinct Tristan Moorhen, Gallinula nesiotis, than to the Common Gallinule. The relationships of the rest of the former Gallinula have not been subject to genetic testing.

Caribbean Coot: Following AOU supplement 57 (2016), the Caribbean Coot, Fulica caribaea, is now treated as a color morph of American Coot, Fulica americana. There was never strong evidence these were separate species.

Finally, if you look at the tree, you may notice Hodgen's Waterhen, Pyramida hodgenorum. It's an extinct species from New Zealand that is not on the TiF list. The monotypic genus Pyramida (Oliver, 1955) takes its name from the Pyramid Valley where many subfossil remains of Hodgen's Waterhen were found. The most recent date to the 1700's. It appears to have once been widespread in New Zealand.

Himantornithini: Bush-hens and Waterhens GR Gray 1871

- Nkulengu Rail, Himantornis haematopus

- Blue-faced Rail, Gymnocrex rosenbergii

- Talaud Rail, Gymnocrex talaudensis

- Bare-eyed Rail, Gymnocrex plumbeiventris

Fulicini: Coots, True Gallinules and Moorhens Nitzsch 1829

- Spot-flanked Gallinule, Porphyriops melanops

- Sora, Porzana carolina

- Spotted Crake, Porzana porzana

- Australian Crake, Porzana fluminea

- Makira Woodhen, Pareudiastes silvestris

- †Samoan Woodhen / Samoan Moorhen, Pareudiastes pacificus

- Black-tailed Native-hen, Tribonyx ventralis

- Tasmanian Native-hen, Tribonyx mortierii

- Lesser Moorhen, Paragallinula angulata

- Dusky Moorhen, Gallinula tenebrosa

- Common Gallinule, Gallinula galeata

- †Tristan Moorhen, Gallinula nesiotis

- Gough Moorhen, Gallinula comeri

- Common Moorhen, Gallinula chloropus

- Red-fronted Coot, Fulica rufifrons

- †Mascarene Coot, Fulica newtonii

- Giant Coot, Fulica gigantea

- Horned Coot, Fulica cornuta

- Red-gartered Coot, Fulica armillata

- Eurasian Coot, Fulica atra

- Red-knobbed Coot, Fulica cristata

- Hawaiian Coot, Fulica alai

- American Coot, Fulica americana

- Slate-colored Coot / Andean Coot, Fulica ardesiaca

- White-winged Coot, Fulica leucoptera

Porphyrioninae Reichenbach, 1849

Although the swamphens are placed next to the gallinules and coots, the genetic distance between them is quite large. Garci-R. and Matzke (2021) estimate that their most recent common ancestor lived about 28 million years ago. This should not now be surprising. Earlier genetic evidence had shown they were quite separated. Ozaki et al. (2010) placed the swamphens sister to Laterallini and Trewick (1997) grouped them with Zapornini. The morphological evidence has also cast doubt on the position of the swamphens, with Livezey (1998) putting them in a relatively basal position.

The swamphens are in the final subfamily, Porphyrioninae. In the current edition of TiF, it contains three tribes: Porphyrionini, Zapornini, and Laterallini. The swamphen tribe Porphyrionini is basal group in subfamily Porphyrioninae.

Porphyrionini

The first tribe of Porphyrioninae, Porphyrionini, is mainly composed of purple gallinules (Porphyrula) and swamphens (Porphyrio). Morphological data suggests that Aphanocrex belongs in this tribe too. Indeed, Livezey's (1998) analysis suggested that the extinct St. Helena Rail, Aphanocrex podarces, might even be embedded in Porphyrula, while Garcia-R. and Matzke's (2021) combined molecular/morphological analysis put them as the basal bird in Porphyrionini.

American purple gallinules: Olson (1973) had recommended that the American purple gallinule genus, Porphyrula, be merged into Porphyrio. Trewick (1997) made a genetic case for this merger, which was adopted by AOU in 2002. However, Garcia-R and Matzke (2021) found that common ancestor of the two genera lived over 8 mya. As a result, the purple gallinules

- Allen's Gallinule, Porphyrio alleni

- Purple Gallinule, Porphyrio martinica

- Azure Gallinule, Porphyrio flavirostris

have been restored to Porphyrula (Blyth, 1852), type alleni.

Purple Swamphens: Based on the genetic analysis of Garcia-R. and Trewick (2015) and the earlier papers by Sangster (1998) and Sangster et al. (1999), the Purple Swamphen, Porphyrio porphyrio has been split into 5 species:

- Western Swamphen, Porphyrio porphyrio,

- Black-backed Swamphen, Porphyrio indicus, including viridis,

- Australasian Swamphen, Porphyrio melanotus, including melanopterus palliatus, bellus, samoensis, vitiensis, and pelewensis,

- Gray-headed Swamphen, Porphyrio poliocephalus, including caspius and seistanicus,

- Philippine Swamphen, Porphyrio pulverulentus.

Laterallini

The next tribe is Laterallini, the tribe of New World crakes. It's composition remains pretty much the same as before, except for transferring the St. Helena Crake, Zapornia astrictocarpus (Zapornini) to genus Laterallus (GR Gray, 1855), type melanophaius.

Rufirallus: I have resurrected Rufirallus (Bonaparte 1854, type viridis) for the Russet-crowned Crake, Rufirallus viridis. Based solely on morphological data, Garcia-R. and Matzke (2021) group it with the Rusty-flanked Crake, Laterallus levraudi and Ruddy Crake, as Rufirallus ruber. However, genetic data from Kirchman et al. (2021) indicates that the Ruddy Crake belongs elsewhere. Genetic data is almost invariably superior. Using a sparser data set, Kirchman et al. found it closer to albigularis than to melanophaius, and I have repositioned it accordingly on the Garcia-R. and Matzke tree. I wasn't sure whether to bring levraudi with it. Without a compelling reason to move it, I left it sister to viridis.

Whether the above is correct or not, the Russet-crowned Crake, type species of Rufirallus, is closely related to the Ocellated Crake, Micropygia schomburgkii. Micropygia and Rufirallus form the basal claed in Laterallini.

More genus changes: Here are the changes of genus for the rest of Laterallini:

- The Ascension Crake, Mundia elpenor joins the black rail genus Creciscus (Cabanis, 1857), type jamaicensis.

- The White-throated Crake, Limnocrex albigularis, is transferred to Laterallus (GR Gray, 1855), type melanophaius.

- The Gray-breasted Crake, Laterallus exilis is sister to the Yellow-breasted Crake, Hapalocrex flaviventer. However, they are distant relations, so a new genus is needed. I don't know of any with exilis as type, so a temporary name must be used. Gray-breasted Crake becomes "Hapalocrex" exilis.

The next branch contains Swinhoe's and Yellow Rails (Coturnicops).

After that, the picture becomes much murkier. Stervander et al. (2019), Garcia-R et al. (2020), Garcia-R. and Matzke (2021), and Kirchman et al. (2021) have all weighed in on this, and their results can't really be reconciled. Because Garcia-R. and Matzke use the most data, I have followed a lightly modified form of their tree for the rest of Laterallini.

In Garcia-R and Matzke (2021), the next branch consists of the Yellow-breasted Crake, Hapalocrex flaviventer and the Gray-breasted Crake. These seem rather distinct, and are separated by about 8 million years (Gracia-R. and Matzke), so I've put them in separate genera. Unusually for the rails, there's no genus name available, so I'm referring to the Gray-breasted Crake as "Hapalocrex" exilis. Note that Stervander et al. (2019) have both exilis and flaviventer in Laterallus. Further, both Garcia-R and Matzke (with morphology) and Garcia-R. et al. (2020, genes only), have the Rufous-sided Crake, Laterallus melanophaius and Red-and-white Crake, Laterallus leucopyrrhus as sister species. Kirchman et al. (2021) have a very different take on this. The other papers don't consider both of them.

The rest of Laterallini are either in Laterallus or Creciscus. This includes the Black-banded Crake, Laterallus fasciatus, which has been moved from Rufirallus (or Porzana or Anurolimnas, depending on the taxonomy used). I suspect there will be further changes in the clade as the other taxa are sampled, and we may need to recut the genera too. Laterallus in Garcia-R. and Matzke is estimated to have had a common ancestor about 5 mya, so I treat it as a single genus. However, moving ruber there may have changed matters, but that will have to wait for a more comprehensive study of the clade.

Raty's reanalysis grouped together a few species that look like Black Rail (jamaicensis). Most importantly, it included the Speckled Rail, Creciscus notatus, which doesn't seem to be in any published molecular phylogeny. The Galapagos Rail belongs here too (Chaves et al., 2020). The old name Creciscus (Cabanis 1857, type jamaicensis) applies to the group, which also contains the Ascension Crake, Creciscus elpenor. On morphological grounds, the Inaccessible Island Rail, Creciscus rogersi, and the St. Helena Crake, Creciscus astrictocarpus also belong to this group.

Zapornini

The last tribe to consider is Zapornini, which combines the old Zapornini with almost all of the old Himantornithini, Himantornis itself excepted. Zapornini contains a number of Old World crakes, some of them once place in Porzana.

There are a number of genus changes that affect Zapornini.

- The Isabelline Bush-hen, Amaurornis isabellina, seems a bit distant from the other Amaurornis and becomes the monotypic genus Oenolimnas (Sharpe, 1853).

- The Brown Crake, Zapornia akool, is transferred to Limnocorax (W Peters, 1854), type flavirostra.

- Finally, a group of former Zapornia (and before that Porzana)

have been separated as the genus Pennula (Dole, 1878), type

sandwichensis. They are:

- Sakalava Rail, Zapornia olivieri

- Black-tailed Crake, Zapornia bicolor

- Hawaiian Rail, Zapornia sandwichensis

- Red-eyed Crake, Zapornia atra

- Spotless Crake, Zapornia tabuensis

- Kosrae Crake, Zapornia monasa

- Tahiti Crake, Zapornia nigra

There are two parts to Zapornini. The first is the remains of the old Himantornithini. This clade constains the Watercock, various Bush-hens, and the White-breasted Waterhen, Amaurornis phoenicurus.

The other part starts with what remains of Rallina. The phylogeny for the rest is based on Slikas et al. (2002), except for the Maui Crakes, which are placed based on morphology. Amazingly, part 3 of Figure 2 forms a nice block that can just be dropped into the tree, and that is what I did.

Many of the other species in this clade were previously classified in genus Porzana, but were then moved to Zapornia (Leach 1816, type Gallinula minuta Montagu 1813 = parva). Given the genetic distances involved, I've separated the Ruddy-breasted Crake and Band-bellied Crake in genus Limnobaenus (Sundevall 1873, type fuscus); and also the Black Crake as Limnocorax flavirostra (W. Peters, 1854) along with the Brown Crake, now Limnocorax akool. The remaining species then fall into two groups. Again, there is substantial distance between them, and they are the remaining Zapornia and the birds just transferred to Pennula.

Porphyrionini: Purple Gallinules and Swamphens Reichenbach, 1849

- †St. Helena Rail, Aphanocrex podarces

- Allen's Gallinule, Porphyrula alleni

- Purple Gallinule, Porphyrula martinica

- Azure Gallinule, Porphyrula flavirostris

- Western Swamphen, Porphyrio porphyrio

- Black-backed Swamphen, Porphyrio indicus

- African Swamphen, Porphyrio madagascariensis

- South Island Takahe, Porphyrio hochstetteri

- †North Island Takahe, Porphyrio mantelli

- Australasian Swamphen, Porphyrio melanotus

- Gray-headed Swamphen, Porphyrio poliocephalus

- Philippine Swamphen, Porphyrio pulverulentus

- †White Swamphen / Lord Howe Swamphen, Porphyrio albus

Laterallini: New World Crakes Kirchner et al., 2021

- Ocellated Crake, Micropygia schomburgkii

- Russet-crowned Crake, Rufirallus viridis

- Rusty-flanked Crake, Rufirallus levraudi

- Swinhoe's Rail, Coturnicops exquisitus

- Yellow Rail, Coturnicops noveboracensis

- Yellow-breasted Crake, Hapalocrex flaviventer

- Gray-breasted Crake, "Hapalocrex" exilis

- Ruddy Crake, Laterallus ruber

- White-throated Crake, Laterallus albigularis

- Rufous-faced Crake, Laterallus xenopterus

- Black-banded Crake, Laterallus fasciatus

- Rufous-sided Crake, Laterallus melanophaius

- Red-and-white Crake, Laterallus leucopyrrhus

- Speckled Rail, Creciscus notatus

- Black Rail, Creciscus jamaicensis

- Galapagos Rail / Galapagos Crake, Creciscus spilonota

- Dot-winged Crake, Creciscus spiloptera

- †St. Helena Crake, Creciscus astrictocarpus

- †Ascension Crake, Creciscus elpenor

- Inaccessible Island Rail, Creciscus rogersi

Zapornini: Old World Crakes Reichenbach, 1849

- White-browed Crake, Poliolimnas cinereus

- New Guinea Flightless Rail, Megacrex inepta

- Striped Crake, Aenigmatolimnas marginalis

- Watercock, Gallicrex cinerea

- Isabelline Bush-hen, Oenolimnas isabellinus

- White-breasted Waterhen, Amaurornis phoenicurus

- Plain Bush-hen, Amaurornis olivacea

- Talaud Bush-hen, Amaurornis magnirostris

- Pale-vented Bush-hen, Amaurornis moluccana

- Slaty-legged Crake, Rallina eurizonoides

- Red-necked Crake, Rallina tricolor

- Andaman Crake, Rallina canningi

- Red-legged Crake, Rallina fasciata

- Ruddy-breasted Crake, Limnobaenus fuscus

- Band-bellied Crake, Limnobaenus paykullii

- Black Crake, Limnocorax flavirostra

- Brown Crake, Limnocorax akool

- Little Crake, Zapornia parva

- Baillon's Crake, Zapornia pusilla

- †Laysan Rail, Zapornia palmeri

- Black-tailed Crake, Pennula bicolor

- Sakalava Rail, Pennula olivieri

- †Hawaiian Rail, Pennula sandwichensis

- Spotless Crake, Pennula tabuensis

- †Kosrae Crake, Pennula monasa

- Red-eyed Crake / Henderson Crake, Pennula atra

- †Tahiti Crake, Pennula nigra