The information below includes the date and a brief description of each significant change, a link to the relevant page, and that page's new version number. Neither minor spelling corrections nor additions to the references are noted on this page.

Archives of ‘What's New’ Items

The updates for 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019-2022, 2023, and 2024, have been archived separately.

2025 Additions and Subtractions

Based on scientific names.

2025 Splits (12)

- Huon Bowerbird, Amblyornis germanus, has been split from MacGregor's Bowerbird, Amblyornis macgregoriae.

- Solomons Robin, Petroica polymorpha, including subspecies septentrionalis, kulambangrae, and dennisi, has been split from Pacific Robin, Petroica pusilla.

- Black-capped Robin, Heteromyias armiti, including rothschildi, has been split from Ashy Robin, Heteromyias albispecularis.

- Red-throated Rock Martin, Ptyonoprogne rufigula is split from Rock Martin, Ptyonoprogne fuligula

- Pacific Swallow, Hirundo javanica is split from Tahiti (Pacific) Swallow, Hirundo tahitica

- European Red-rumped Swallow, Cecropis rufula, is split from Red-rumped Swallow, Cecropis daurica

- Madagascan Martin, Riparia cowani

- St. Lucia Thrasher, Ramphocinclus sanctaeluciae has been split from White-breasted Thrasher, Ramphocinclus brachyurus.

- Chinese Long-tailed Rosefinch, Uragus lepidus

- Red Crossbill, Loxia minor

- Cassia Crossbill, Loxia sinesciuris

- Two-barred Crossbill, Loxia bifasciata

2025 Lumps (3)

- Red-rumped Swallow, Cecropis daurica is merged into Eastern Red-rumped Swallow, Cecropis daurica

- Scottish Crossbill, Loxia scotica, has been merged into the Common Crossbill, Loxia curvirostra

- Parrot Crossbill, Loxia pytyopsittacus, has been merged into the Common Crossbill, Loxia curvirostra

2025 English Name Changes (10)

- Yellow-legged Flycatcher / Yellow-legged Flyrobin, Microeca griseoceps, becomes Yellow-legged Flyrobin.

- Lemon-bellied Flycatcher / Lemon-bellied Flyrobin, Microeca flavigaster, becomes Lemon-bellied Flyrobin.

- Blue Crested-flycatcher / African Blue-flycatcher, Elminia longicauda, becomes African Blue Flycatcher

- Blue-and-white Crested-flycatcher / White-tailed Blue-flycatcher, Elminia albicauda, becomes White-tailed Blue Flycatcher

- Rock Martin, Ptyonoprogne fuligula, becomes Large Rock Martin

- Pacific Swallow, Hirundo tahitica becomes Tahiti Swallow

- Red-rumped Swallow, Cecropis daurica becomes Eastern Red-rumped Swallow

- White-breasted Thrasher, Ramphocinclus brachyurus, becomes Martinique Thrasher.

- Long-tailed Rosefinch, Uragus sibiricus, becomes Siberian Long-tailed Rosefinch

- Red Crossbill, Loxia curvirostra, becomes Common Crossbill

2025 Other Changes (4)

- Grauer's Warbler, Graueria vittata, has moved from Macrosphenidae to Acrocephalidae

- Three subspecies of Red-rumped Swallow, Cecropis daurica are merged with West African Swallow Cecropis domicella to create African Red-rumped Swallow, Cecropis melanocrissus

- The genus Erythrogenys has been replaced by Megapomatorhinus

- The Ruby-crowned Kinglet has been moved to genus Corthylio, becoming Corthylio calendula.

IOC English Names

Although I started with the Howard-Moore list, I am now using the IOC list as a baseline. Every species gets an IOC-style name. That doesn't mean its the only name, or that it exactly matches the IOC name. Four percent of the species have two names. This usually happens because of differences between the IOC name and the AOU name (NACC or SACC). In such cases, I usually give the IOC name second, even in cases where I think the AOU name is stupid (E.g., redstarts for the Myioborus whitestarts). A few other non-IOC names have also been retained.

Some IOC-style names don't exactly match the true IOC name due to differences in taxonomy. For example, the IOC recognizes two species of Laniisoma—Brazilian Laniisoma and Andean Laniisoma. In this case, I currently follow SACC taxonomy which has only one Laniisoma. However, their English name is entirely different (Shrike-like Cotinga). Keeping in mind that the species has been known as the Elegant Mourner, I added the IOC-ish English name Elegant Laniisoma.

The IOC-style names have been fully Americanized (gray, not grey; AOU-style hyphenation). I'm also a little more aggressive than AOU in adding hyphens to break up two-part names that don't scan well. I also favor hyphens when it makes the “last name” of the bird clear. Hyphens greatly improve the results when sorting bird names by last name. I know some people fight flame wars about it, but to me, bird names that differ only in hyphenation and/or American vs. British spelling, such as Grey Pileated Finch and Gray Pileated-Finch, are essentially identical (and are the IOC name).

June 2025

June 26

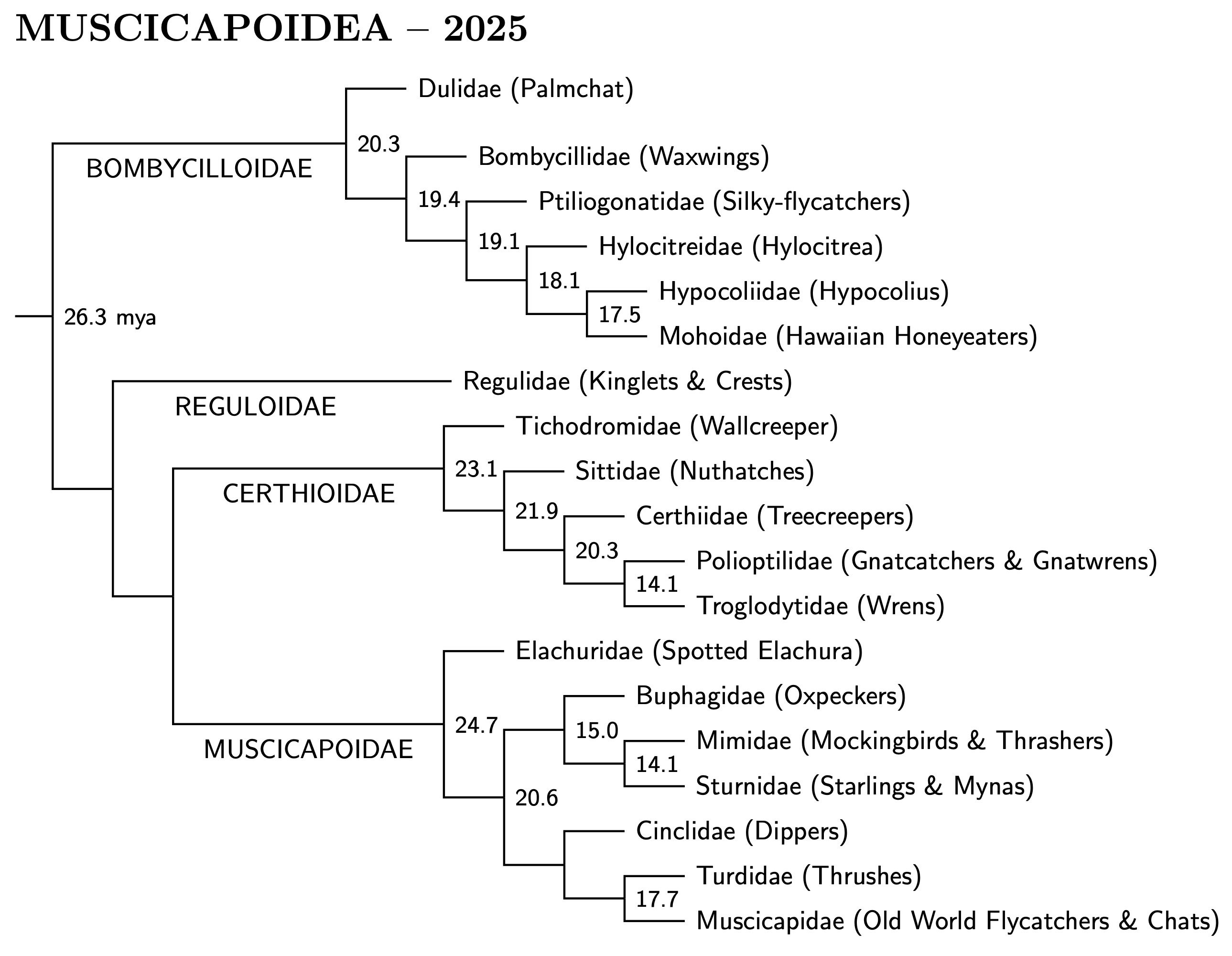

I had originally broken up the clade containing Muscicapidae into four

superfamilies because of uncertainty about the relations between them.

With the publication of the “big three” papers: Oliveros et

al. (2019), Kuhl et al. (2021), and Stiller et al. (2024) most of the

uncertainty has been eliminated. A reorganization of the clade is

now warranted, and I have demoted the four superfamilies to epifamilies:

Bombycilloidae, Reguloidae, Certhiodae, and Muscicapoidae. The smallest

clade containing them is now named Muscicapoidea. It is sister to

Passeroidea, putting it on more equal terms with Sylvioidea and

Passeroidea. Details of the differences between the big three are

discussed further in the Muscicapoidea section.

[Muscicapoidea Muscicapoidea I, Bombycilloidae and Reguloidae 3.49]

|

| Big Muscicapoidea tree |

|---|

Bombycilloidae changes:

As mentioned before, the Spotted Elachura has been removed from

Bombycilloidae to Muscicapoidae. Based on Oliveros et al. (2019) and Zhao

et al. (2025), Hylocitrea and Hypocolius are now in

separate families. The families in Bombycilloidae are arranged as in

Oliveros et al. The phylogeny within each family follows Zhao et al. The

one change this makes is for Mohoidae.

[Bombycilloidae Muscicapoidea I, Bombycilloidae and Reguloidae 3.49]

Ruby-crowned Kinglet:

According to both Päckert et al. (2012b) and Oliveros et al. (2019)

the most common recent ancestor of the Ruby-crowned Kinglet and the

other kinglets lived about 12 million years agot. Accordingly, I've put

the Ruby-crowned Kinglet in the monotypic genus Corthylio Cabanis

1853. That makes it Corthylio calendula.

[Regulidae Muscicapoidea I, Bombycilloidae and Reguloidae 3.49]

June 24

Elachuridae:

Elachuridae has been moved to the basal position in the epifamily

Muscicapoidae. See Oliveros et al. (2019) and Stiller et al. (2024).

Elachuridae was not included in Kuhl et al.'s (2021) analysis.

[Mimidae Muscicapoidea III, Elachuridae through Sturnidae 3.49]

June 21

White-breasted Thrasher:

The White-breasted Thrasher, Ramphocinclus brachyurus, has been split

into Martinique Thrasher, Ramphocinclus brachyurus, and St. Lucia

Thrasher, Ramphocinclus sanctaeluciae.

[Mimidae Muscicapoidea III, Elachuridae through Sturnidae 3.48]

June 20

Eurostopodus Nightjars:

McCullough et al. (2025) includes a complete phylogeny for Eurostopodidae

based on ultraconserved elements. Although undated, they phylogeny also

provided additional support for the current TiF arrangement, putting

Eurostopodus, Lyncornis, and Gactornis on separate

branches (ranked as families) prior to Caprimulgidae. They don't address

the ages of these clades, so I'm sticking with the existing estimates.

[Eurostopodidae Strisores I, Caprimulgiformes etc. 3.51]

June 13

Basal Oscines: I've added a dated phylogeny for the Basal Oscines.

It can been found by clicking on the phylogeny of the Basal Oscines, or by

clicking here.

[Basal Oscines Menuridae through Pomatostomidae, 3.48]

Australasian Treecreepers: There is substantial genetic distance

between the genera Cormobates and Climacteris, so I have

placed in separate subfamilies.

[Climacteridae Menuridae through Pomatostomidae, 3.48]

Bowerbirds: The phylogeny of the Ptilonorhynchidae now follows Ericson et al. (2020). There are two relatively deep divisions in the Ptilonorhynchidae, one at about 15 mya, and another around 12.8 mya. I've treated the first division as creating two subfamilies, Ptilonorhynchinae and Ailuroedinae. The second division divides Ailuroedinae into two tribes, Amblyornithini and Ailuroedini. I've divided them this in order to emphasize that the Australasian catbirds are more closely related to some bowerbirds than others.

The revised phylogeny enabled me to restore the genus Prionodura De Vis 1883 for the Golden Bowerbird, Prionodura newtoniana. The previous phylogeny required it to be included in Amblyornis.

Finally, I've followed IOC and split the Huon Bowerbird, Amblyornis

germanus, from MacGregor's Bowerbird, Amblyornis macgregoriae,

IOC had split them based on distinctive bower construction and

unspecified DNA differences, citing Beehler and Pratt (2016) and Gregory

(2017). They didn't cite Ericson et al. (2020), who provided a dated

phylogeny of the bowerbirds. They estimated the split between the two

taxa occurred in the early Pleistocene, over 2 mya. This is a strong

indication they are separate species.

[Ptilonorhynchidae Menuridae through Pomatostomidae, 3.48]

Pardalotes and Gerygones: I've finally been convinced to treat the

Pardalotes (Pardalotidae) and Gerygones (Acanthizidae) as separate

families. The paradolotes are older than I thought.

[Pardalotidae Menuridae through Pomatostomidae, 3.48]

June 6

I've added a dated phylogeny for the waterbird clade Ardeae

(Eurypygimorphae plus Aequornithes). Most of the ages are averages of

Kuhl et al. (2021) and Stiller et al. (2024). The two phylogenies differ

slightly for the Pelecaniformes, and I have used Stiller et al.'s

phylogeny and ages. I considered Stiller et al.'s ages likely wrong for

the Procellariiformes, and have used Kuhl et al.'s ages there.

[Ardeae I Eurypygimorphae & Aequornithes I, 3.50]

The only real change is the order of families in the Pelecaniformes,

where the Balaenicipitidae (Shoebill) now comes first.

[Ardeae II Aequornithes II, 3.50]

June 2

It turns out that Mathews was sometimes spelled Matthews in the TiF list. I think I corrected them all.

May 2025

May 31

English Name Changes (2)

- The English name of Microeca griseoceps is changed from Yellow-legged Flycatcher / Yellow-legged Flyrobin to Yellow-legged Flyrobin.

- The English name of Microeca flavigaster is changed from Lemon-bellied Flycatcher / Lemon-bellied Flyrobin to Lemon-bellied Flyrobin.

Genus Changes (+4, -2)

Unlike BoW, I don't think it makes sense to put the Black-chinned Robin, Poecilodryas brachyura, in genus Leucophantes. It appears to fit comfortably in Poecilodryas, and I have left it there. I have also chosen to keep the distinctive Banded Yellow Robin in genus Gennaeodryas rather than include it in Eopsaltria.

- The Canary Flyrobin, Microeca papuana, is moved to the monotypic genus Devioeca Mathews 1925. (corrected)

- The Olive Flyrobin, Microeca flavovirescens, and Yellow-legged Flyrobin, Microeca griseoceps, are placed genus Kempiella Mathews 1913, type K. griseoceps kempi.

- The Yellow-bellied Flyrobin, Microeca flaviventris, has been placed in the monotypic genus Cryptomicroeca Christidis, Irestedt, Rowe, Boles and Norman 2012.

- The Torrent Flyrobin, Microeca muelleriana, has been placed in the monotypic genus Monachella Savadori 1874.

- The genera Peneoenanthe and Peneothello have been absorbed by genus Melanodryas Gould 1865, type cucullata.

Splits (2)

- Solomons Robin, Petroica polymorpha, including subspecies septentrionalis, kulambangrae, and dennisi, has been split from Pacific Robin, Petroica pusilla. See Kearns et al. (2016, 2018, 2019, 2020).

- Black-capped Robin, Heteromyias armiti, including rothschildi, has been split from Ashy Robin, Heteromyias albispecularis, based on genetics, plumages, and calls. See Christidis et al. (2011), Beehler and Pratt (2016), and Gregory (2017).

[Petroicidae Basal Passerida, 3.48]

May 7

I've updated age estimates for the origin and crown clade of

Passeriformes based on Oliveros et al. (2019), Kuhl et al. (2021),

Stiller et al. (2024), and the very recent paper by Luo et al. (2025).

This replaced previous speculations about the ages of Passeriformes and

its suborders.

[Passerine Evolution, PasseriformeS I, 3.48]

May 1

The Nechisar Nightjar, Caprimulgus solala, has been removed from

the TiF list. Shannon, van Grouw, and Collinson, (2025) extracted DNA

from the only specimen, a left wing. They found that it was a hybrid.

More precisely, its mother was a Standard-winged Nightjar, Caprimulgus

longipennis. The identity of the father was not. Its father's

identity remains unknown. We do it is one of the nightjars that have not

yet been sequenced. However, on morphological grounds, the father is

believed to have been a Freckled Nightjar, Caprimulgus tristigma.

[Caprimulgidae, Strisores I, 3.50]

The Brushland Tinamou, Rhynchotus cinerascens becomes Paranothoprocta cinerascens. It is the only member of the new genus Paranothoprocta, introduced by Bertelli, Almeida, and Giannini (2025).

The genus Cryptura, Vieillot 1816, is replaced by Crypturus, Illiger 1811. Both have type major. I had erroneously thought the type of Crypturus was cinereus, but it is actually a replacement for Tinamus Latham 1790, which has type major. As a result, I've replaced the previous Crypturus with Crypturornis Oberholser 1922, which really does have type cinereus.

March 2025

March 19

The genus Erythrogenys was never actually made available, as it is

based on the misreading of a comment by Hodgson 1836. The correct name

for that scimitar-babbler genus is Megapomatorhinus, Moyle et al.

(2012). It has type hypoleucos.

[Sylvioidea III, 3.51]

March 16

Sylvioidea reordered:

I've reordered the families in Sylvioidea based on a combination of

Oliveros et al. (2019), Kuhl et al. (2021), and Stiller et al. (2024).

As a result, Paroidea shrank to two families, and was subsumed into

Sylvoidea, along with Hyliotidae and Stenostiridae (in that order).

I've also demoted Alcippeidae to a subfamily of Leiothrichidae.

See the diagram for latest current arrangement.

I will revisit the genera and species later.

[Sylvioidea I, 3.50]

[Sylvioidea II, 3.50]

[Sylvioidea III, 3.50]

Alcippeidae now subfamily Alcippeinae:

I've demoted Alcippeidae to a subfamily of Leiothrichinae. I'd ranked

Alcippeidae as a family because it was unclear whether it grouped with

Leiothrichidae or Pellorneidae. Cai et al. (2019, 2020) sequenced all of

Alcippeidae, and their results make it clear it is sister to

Leiothrichidae.

[Sylvioidea III, Sylvioidea III, 3.50]

Elminia Blue Flycatchers:

I've removed the Crested-Flycatcher names from the true Elminia,

leaving only the Blue Flycatcher names. The hyphens are removed to avoid

confusion with Cyornis. Thus

Blue Crested-flycatcher / African Blue-flycatcher,

Elminia longicauda, becomes African Blue Flycatcher and

Blue-and-white Crested-flycatcher / White-tailed Blue-flycatcher,

Elminia albicauda, becomes White-tailed Blue Flycatcher.

[Stenostiridae, Sylvioidea I, 3.50]

Grauer's Warbler:

Grauer's Warbler, Graueria vittata, has moved from Macrosphenidae

to Acrocephalidae, where it gets its own subfamily Graueriinae. The

remaining Acrocephalidae become subfamily Acrocephalinae.

[Acrocephalidae, Sylvioidea I, 3.50]

Forest Swallow Correction:

De Silva et al. (2018) discovered that the Forest Swallow, formerly in

genus Petrochelidon, was actually sister to the Delichon

swallows. They attempted to establish the new genus

‘Atronanus’ for it, but didn't preregister it with

ZooBank as is required for electronic changes to nonmenclature. As a

result, I'm referring to the Forest Swallow as ‘Atronanus’

fuliginosus.

[Hirundinidae, Sylvioidea II, 3.50]

February 2025

February 9

I found the following on BirdForum: “My question, however, was why use minor instead of the older name pusilla?” The short answer to that is that I used the IOC list and they don't list pusilla as one of the subspecies. I figured there must a reason they don't use it, so I started digging, and ended up finding one.

I began with Peters, which immediately led to Gloger 1834, who introduced the name pusilla. That work is available on the Internet Archive. It's in German, which I fed to Google Translate. Gloger referred to something by Lichtenstein in lieu of a description.

So I went back to Google, and soon found Payne (1987), which addresses the question of minor and pusilla. There's no type specimen for pusilla, and only Georgia as the location (the US state, not the country). Stresemann designated a lectotype in 1922. Payne examined that and a number of other specimens.

Payne wrote: “Gloger's reference to Lichtenstein was evidently to an unpublished manuscript name. Although two reviewers suggested to me that the name may be a nomen nudum, the publication by Gloger constitutes a description, even though it is not as detailed as in certain other taxonomic descriptions or in current practice. The publication is available insofar as it meets the 1985 Code's Article 12 (Names published before 1931 .-(a) Requirements).”

I don't know about the 1985 Code, but I think the current Code agrees with the reviewers. The name would seem to fall under article 12.1.1 about bibliographic references. It requires publication, and Lichtenstein's manuscript, whatever it was, was not published. I think IOC is correct to leave out pusilla, and BOW is wrong to include it. Because of this, I will continue to use Loxia minor for the North American clade of plain-winged crossbills.

February 23, 2025

Swallows: I've updated the Hirundinidae, primarily based on Schield et al. (2024). This includes adding a species tree.

2025 Genus changes: De Silva et al. (2018) discovered that the Forest Swallow, formerly in genus Petrochelidon, was actually sister to the Delichon swallows. They established the new genus Atronanus for it. That makes the Forest Swallow Atronanus fuliginosa.

H&M-4 had already split Phedina into 3 monotypic genera. This is consistent with Schield et al. (2024). As a result, the Banded Martin, Phedina cincta, becomes Neophedina cincta (Roberts 1922) and Brazza's Martin, Phedina brazzae, becomes Phedinopsis brazzae (Wolters 1971).

2025 Species changes: The Rock Martin, Ptyonoprogne fuligula has been split into Large Rock Martin, Ptyonoprogne fuligula, and Red-throated Rock Martin, Ptyonoprogne rufigula. The Large Rock Martin consists of the more southern subspecies anderssoni, fuligula, and pretoriae. The Red-throated Rock Martin has the northern subspecies pusilla, bansoensis and rufigula. See Brown (2019).

The Pacific Swallow, Hirundo tahitica, has been split into Tahiti Swallow, Hirundo tahitica and Pacific Swallow, Hirundo javanica based on morphological differences (HBW/BirdLife).

There are a complex set of changes to the Red-rumped Swallows (Cecropis).

- The monotypic European Red-rumped Swallow, Cecropis rufula, is split from Red-rumped Swallow, Cecropis daurica.

- Three subspecies of Red-rumped Swallow, melanocrissus, kumboensis, and emini are merged with the West African Swallow Cecropis domicella. Both the commmon and scientific names change, giving us African Red-rumped Swallow, Cecropis melanocrissus.

- The remaining subspecies of Red-rumped Swallow, Cecropis daurica: daurica, japonica, nipalensis, and erythropygia join with all four subspecies of Striated Swallow, Cecropis striolata, to create the Eastern Red-rumped Swallow, Cecropis daurica. The name daurica has priority over striolata.

Finally, the Madagascan Martin, Riparia cowani, has been split from the Brown-throated Martin Riparia paludicola. Shield et al. (2024) found they split a healthy 3.3 million years ago. BoW and HBW/BirdLife support the split based on morphology and vocalizations. [Hirundinidae, Sylvioidea II, 3.50]

February 6

Long-tailed Rosefinch:

Long-tailed Rosefinch, Uragus sibiricus is split into Siberian

Long-tailed Rosefinch, Uragus sibiricus, including

sanguinolentus and ussuriensis, and Chinese Long-tailed

Rosefinch, Uragus lepidus, including henrici, based on Liu

et al. (2020). They suggest synonymizing ussuriensis with

sanguinolentus, although IOC has not followed that suggestion.

[Fringillidae, Core Passeroidea II, 3.50]

Crossbills:

Scottish and Parrot crossbills have been demoted to subspecies of the new

Common Crossbill, Loxia curvirostra (old world plain-winged

crossbills). New world plain-winged crossbills are still Red Crossbills,

which are now Loxia minor. I've also recognized the Cassia

Crossbill, which AOS did in 2017. I also split the

White-winged Crossbill, Loxia leucoptera into the

White-winged Crossbill, Loxia leucoptera, of North America

and the Two-barred Crossbill, Loxis bifasciata, of Eurasia.

Click here for more.

[Fringillidae, Core Passeroidea II, 3.50]

January 2025

January 8

Blue-headed Quail-Dove:

The first paper from 2025 that I read was Oswald et al. (2025). They were

able to show that Starnoenadinae both deserves subfamily status and is

sister to the subfamily Columbinae.

[Columbidae, Columbiformes II, 3.51]

January 7

Caracaras:

Replacement for changes on Dec. 25:

Fuchs et al. (2015) found that many of the caracaras are

closely related, with their common ancestor estimated to live less than

5 million years ago. The differences between them are not large, so I've

merged the genera Milvago, and Phalcoboenus into

Daptrius. Ibycter is somewhat different, not just because

it is much less closely related to the Daptrius than the

Daptrius are to one another, but in other ways. E.g., the syrinx

is different from that of the Caracaras in the expanded Daptrius.

See also

SACC proposal #1038.

[Falconidae, Basal Australaves, 3.49a]

I've also slighted edited some previous pages, including, but not limited to the issues recently mentioned on BirdForum.