STRISORES Baird, 1858

I use the older term Strisores (Baird 1858) for this group in place of Huxley's Cypselomorphae (1867). This allows the use of Cypselomorphae for a smaller clade, as in Mayr (2010).

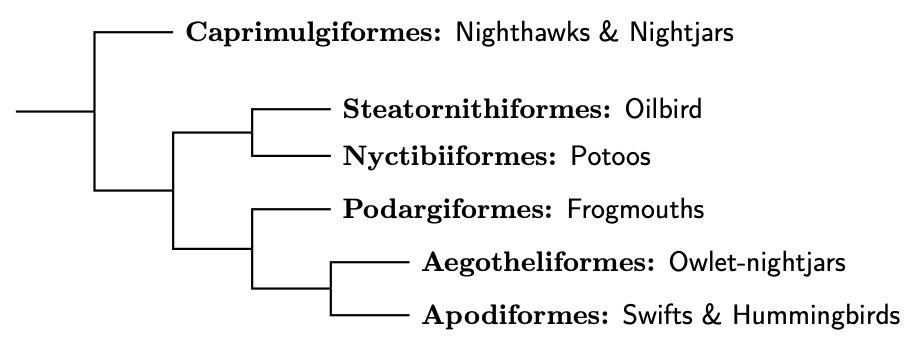

Strisores were previously considered the biggest chunk of Metaves. The breakup of Metaves has made them the biggest chunk of Otidae. Although it is tempting to group all of the non-owl nightbird families in a single order, they do not form a clade. Any clade containing birds such as nightjars, frogmouths and potoos must also contain the swifts and hummingbirds (e.g. Espinosa de los Monteros, 2000; Mayr, 2002; Ericson et al., 2006; Hackett et al., 2008; Prum et al., 2015; Kuhl et al., 2021).

The divisions between the orders of the Strisores are very deep, and DNA studies seem to have converged on the branching order. Until Kimball et al. (2013), the evidence that Strisores even formed a clade was a little shaky. The major divisions within Strisores are quite deep (Prum et al., 2015; Kuhl et al., 2021). Because of this, I consider the corresponding 6 branches as separate orders: Caprimulgiformes (nightjars), Steatornithiformes (oilbird), Nyctibiiformes (potoos), Podargiformes (frogmouths), Aegotheliformes (owlet-nightjars), and Apodiformes (treeswifts, swifts, and hummingbirds) at the end. It was rather a surpise to find the swifts and hummingbirds embedded in clade of night birds.

Until Kimball et al. (2013), the monophyly of the Strisores was only supported by analyses that include β-fibrinogen. More recent larger-scale analyses, including those Prum et al. (2015) and Kuhl et al. (2021), have made it pretty clear Strisores are monophyletic. The orders in Strisores are arranged as in Prum et al. (2015) and Kuhl et al. (2021). Both also estimate that each of the 6 orders are lineages that originated in the Palaeocene or very early Eocene.

| Strisores Phylogeny |

|---|

|

CAPRIMULGIFORMES Ridgway, 1881

The thesis by Han (2006) and the follow-up paper (Han et al., 2010) have done much to clarify the situation within the Caprimulgidae. Sigurðsson's (2013) disseration and the following paper (Sigurðsson and Cracraft, 2014) touched up the overall structure and filled in more of the details. This identified the major groups and allowed me to construct a species tree for the New World nightjars. I have a partial phylogeny for the Old World Nightjars which has influenced the way I order them.

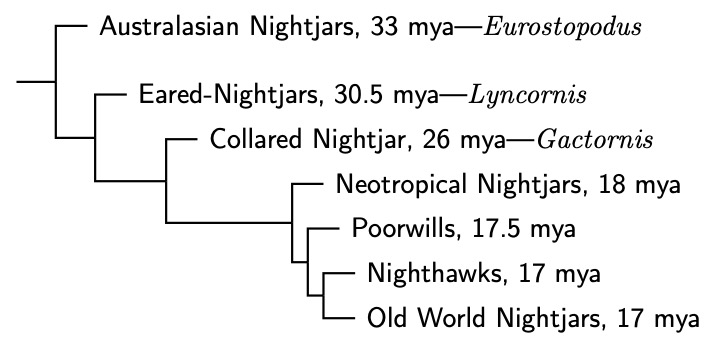

The first of business is to identify the families within Caprimulgiformes. We'll use the following figure to help. The first branch (Eurostopodus) dates to about 33 mya (Prum et al., 2015). Prum et al. put the split between nighthawks and Old World nightjars at about 17 mya. I've used that and the branch lengths in Han et al. (2010) and in Sigurðsson and Cracraft (2014) to estimate ages of the various clades.

Sibley, Ahlquist, and Monroe (1986) noticed its antiquity of Eurostopodus and ranked it as a family, Eurostopodidae. Contra Sangster et al. (2023a), Sibley, Ahlquist, and Monroe did not introduce the name Eurostopodidae. It was first made available a century earlier. In 1886, Bennett used it while commenting on their flight style. However, Bennett did not go on to explain what he meant to include in Eurostopodidae. Sibley et al. were clear that their Eurostopodidae meant just the genus Eurostopodus.

Since then, numerous studies, including Mariaux and Braun (1996), Larsen et al. (2007), and Braun and Huddleston (2009) have shown that E. mystacalis and E. papuensis were not part of the main Caprimulgidae clade (the groups at 17-18 mya). As shown below, they are the first extant branch of the Caprimulgiformes.

But not all Eurostopodus were equal. Han et al. (2010) went a step further. He showed that while the type of Eurostopodus, E. argus grouped with E. mystacalis and E. papuensis, the Great Eared-Nightjar, E. macrotis, was on a separate branch. It needed to be placed in a different genus. Since the type of Lyncornis (cerviniceps) was then considered part of E. macrotis, the Great Eared-Nightjar became Lyncornis macrotis. This has since been confirmed by other studies, including Sigurðsson and Cracraft (2014). Thus Lyncornis is the second branch of the Caprimulgiformes.

There is another complication, the Collared Nightjar, formerly Caprimulgus enarratus is also a separate branch. Han, Robbins, and Braun (2010) created the genus Gactornis for it. The Gactornis branch seems to date to about 26 mya. In constrast, the main body of the Caprimulgiformes doesn't start to expand until about 18 mya. It breaks into four groups.

| Caprimulgiformes Phylogeny |

|---|

|

When we look at the extant groups, we find that Eurostopodus is restricted to Australasia, Lyncornis is in south and southeast Asia, Gactornis in Madagascar, and that the main body seems to have originated in South America. The first two make geographic sense, but how did Gactornis get to Madagascar? Did it fly directly? A map of 31 mya suggest the Maldives, Chagos Archipelago, and the Mascarene Plateau (Seychelles and Mascarenes) were more extensively exposed and could have provided an easy pathway to Madagascar. Alternatively, there could be lost ancestors that expanded into Asia and Africa first.

As Gactornis is sister to the main branch, how did it get to South America? Were there other Gactornis relatives that expanded into Africa, and then crossed a narrower Atlantic 18 mya? Or did they move to Americas earlier, with all intermediate branches dying off? A lot could have happened in that 7 my gap!

Because of both age and the interesting biogeography, it makes sense to divide the Caprimulgiformes into 4 families: Eurostopodidae, Lyncornithidae, Gactornithidae, and a restricted Caprimulgidae. The now restricted Caprimulgidae includes many genera which fall into 4 subfamilies: Neotropical nighthawks and nightjars (Nyctidrominae), an American subfamily containing the poorwills and paruaques (Antrostominae), the nighthawks (Chordeilinae), and a complex group of Old World nightjars (Caprimulginae).

Eurostopodidae: Australasian Nightjars Bennett, 1886

1 genus, 7 species Not HBW Family

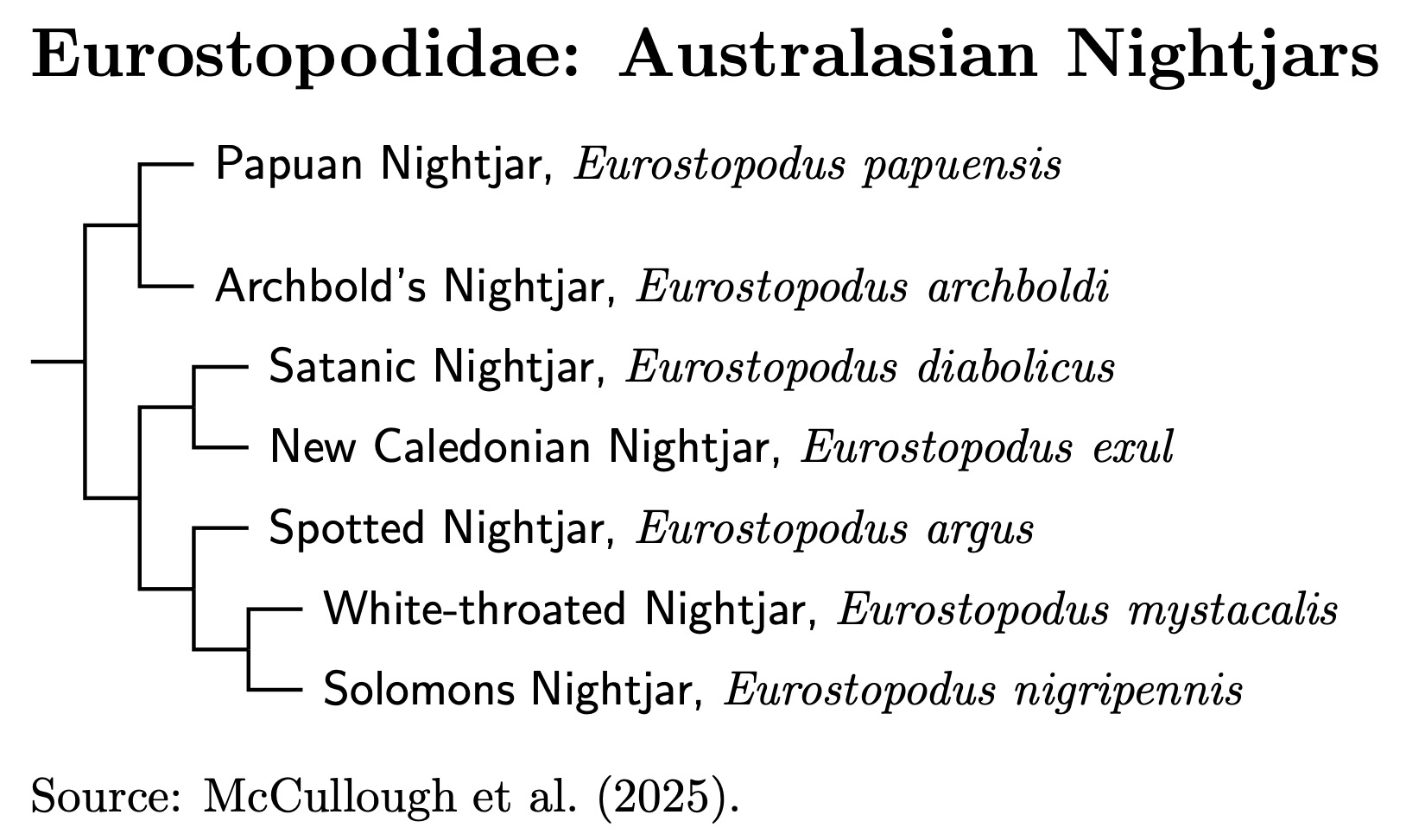

Some species have been added to Eurostopodus since Sibley, Ahlquist, and Monroe (1986). The Solomons Nightjar, Eurostopodus nigripennis, has been split from the White-throated Nightjar, Eurostopodus mystacalis, and the New Caledonian Nightjar, Eurostopodus exul has been added based on a specimen collected in 1939. Both are discussed in Cleere (2010).

Han et al. (2010) and Sigurðsson concur that the Great Eared-Nightjar, formerly placed in Eurostopdus is actually closer to the rest of Caprimulgidae. The Malaysian Eared-Nightjar is morphologically similar, and we are guessing that it is closely related to the Great Eared-Nightjar. Both are moved to the genus Lyncornis. The Papuan Nightjar has sometimes been placed in Lyncornis, but we now know it is more closely related to the other Eurostopodus. Since it's thought to be close to the Archbold's and Satanic Nightjars, I leave them in Eurostopodus.

McCullough et al. (2025) has provided a complete phylogeny for Eurostopodidae based on ultraconserved elements. Although undated, they phylogeny also provided additional support for the TiF arrangement, putting Eurostopodus, Lyncornis, and Gactornis on separate branches prior to the crown clade Caprimulgidae. They don't address the ages of these clades, so I'm sticking with the existing estimates.

| Eurostopodidae: Australasian Nightjars |

|---|

|

As expected, the Papuan Nightjar, Eurostopodus papuensis, which lives in the New Guinea forest below 400m is sister to Archbold's Nightjar, Eurostopodus archboldi, which lives above 1800 m. Surprisingly, the New Caledonian Nightjar, Eurostopodus exul is sister to the Satanic Nightjar, Eurostopodus diabolicus of Sulawesi. The Spotted Nightjar, Eurostopodus argus, is sister to the pair: White-throated Nightjar, Eurostopodus mystacalis and Solomons Nightjar, Eurostopodus nigripennis. The more southern White-throated Nightjars likely migrate between Australia and New Guinea, where some White-throated Nightjars winter.

Eurostopodidae -- Species List

- Papuan Nightjar, Eurostopodus papuensis

- Archbold's Nightjar, Eurostopodus archboldi

- Satanic Nightjar, Eurostopodus diabolicus

- New Caledonian Nightjar, Eurostopodus exul

- Spotted Nightjar, Eurostopodus argus

- White-throated Nightjar, Eurostopodus mystacalis

- Solomons Nightjar, Eurostopodus nigripennis

Lyncornithidae: Eared Nightjars Informal

1 genus, 4 species Not HBW Family

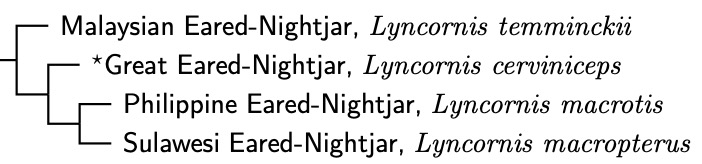

The genus Lyncornis is a also a separate branch of the nightjar tree. I also treat it at family level because it seems to be much closer to Eurostopodus than to the main part of the nightjar tree, which I still call Caprimulgidae.

Sangster et al. (2022a) argued that the Great Eared-Nightjar, Lyncornis macrotis, should be split into 4 species. I'm not convinced by one of those splits due to the similarity of the sonograms, but have accepted the other two. This means that the Great Eared Nightjar is split into three species:

- Great Eared-Nightjar, Lyncornis cerviniceps

- Philippine Eared-Nightjar, Lyncornis macrotis

- Sulawesi Eared-Nightjar, Lyncornis macropterus

| Lyncornithidae |

|---|

|

Lyncornithidae -- Species List

- Malaysian Eared-Nightjar, Lyncornis temminckii

- Great Eared-Nightjar, Lyncornis cerviniceps

- Philippine Eared-Nightjar, Lyncornis macrotis

- Sulawesi Eared-Nightjar, Lyncornis macropterus

Gactornithidae: Collared Nightjar Informal

1 genus, 1 species Not HBW Family

The next surprise is the Collared Nightjar, formerly Caprimulgus enarratus, which seems to be sister to the remaining nightjars and nighthawks. Han et al. (2010) established the new genus Gactornis for it. Sigurðsson and Cracraft (2014) agree that it is the next branch of the Caprimulgidae.

Gactornithidae -- Species List

- Collared Nightjar, Gactornis enarratus

Caprimulgidae: Nightjars, Nighthawks Vigors, 1825

22 genera, 90 species HBW-5

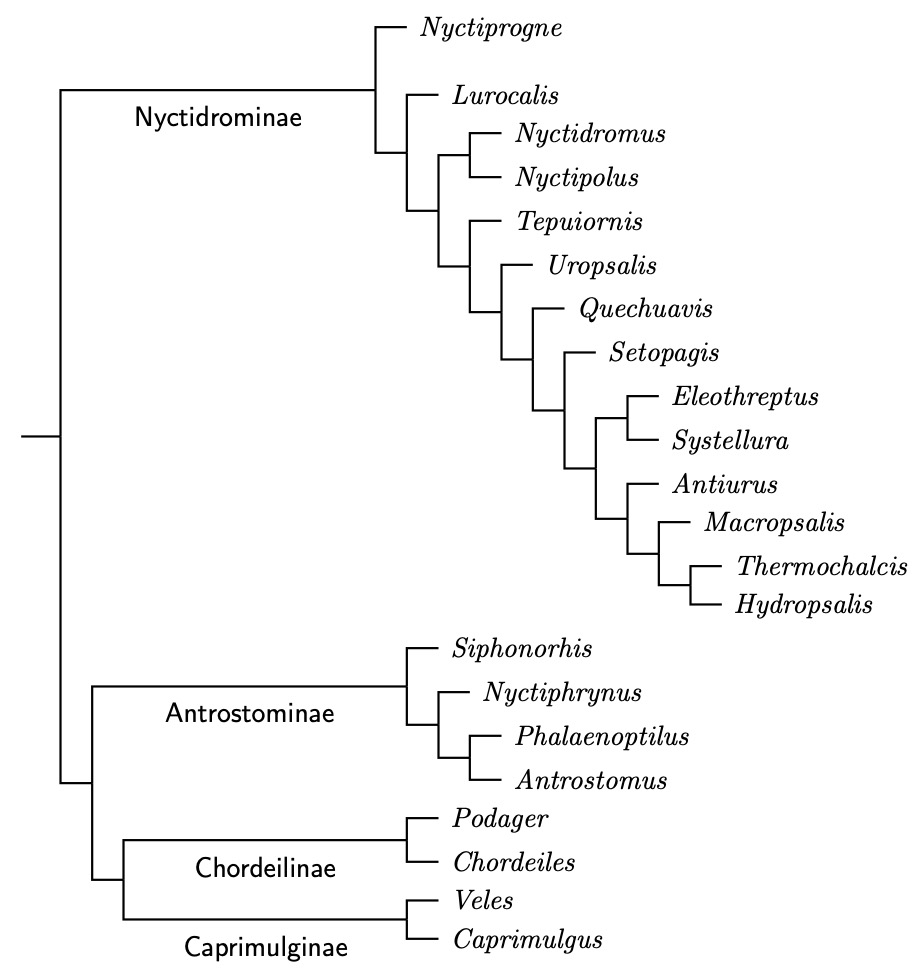

The remaining Caprimulgidae fall into 4 groups, a group of Neotropical nighthawks and nightjars (Nyctidrominae), an American group containing the poorwills and paruaques (Antrostominae), the nighthawk group (Chordeilinae), and a complex group of Old World nightjars (Caprimulginae).

| Caprimulgidae Genera |

|---|

|

| Click for partial species tree |

Han (2006) had previously examined 3 genes, while Barrowclough et al. (2006) examined another (RAG-1). Sigurðsson (2013) included 4 genes, two of them novel. It seems clear enough that the Chordeiles nighthawks and the Old World nigthjars are sister groups. The relative arrangement of the other two with the Neotropical nightjars first, followed by the poorwills, and the the nighthawks and Old World nightjars seems to be the best bet, but there is a lack of consensus among the various genes, and more data might change the picture.

Nyctidrominae: Neotropical Nightjars Cassin, 1851

The first group is Nyctidrominae, a collection of Neotropical Nightjars. The generic limits have changed again here. I had been using different generic limits while the AOU's South American Checklist Committee deliberated on how to best incorporate Han et al. (2010). See SACC proposals #465, #501, and #522. Now that they have decided, the Sigurðsson dissertation comes along and emphasizes that this arrangement renders Setopagis paraphyletic.

The next best option was to submerge Setopagis, Eleothreptus, Systellura, and Macropsalis into Hydropsalis. That was done here in about 2013. Since then, additional genera were defined in 2023, and we can use a set of genera that separates nightjars that appear different, while conforming to the phylogeny in Sigurðsson and Cracraft (2014).

| Neotropical Nightjar Genera | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Type Species | Author | Year |

| Nyctiprogne | minutus | Bonaparte | 1857 |

| Lurocalis | nattererii | Cassin | 1851 |

| Nyctidromus | derbyanus | Gould | 1838 |

| Nyctipolus | nigrescens | Ridgway | 1912 |

| Tepuiornis | whitelyi | Costa et al. | 2023 |

| Uropsalis | lyra | W. DeWitt Miller | 1915 |

| Quechuavis | decussata | van Els et al. | 2023 |

| Setopagis | parvula | Ridgway | 1912 |

| Eleothreptus | anomala | GR Gray | 1840 |

| Systellura | ruficervix | Ridgway | 1912 |

| Antiurus | maculicaudus | Ridgway | 1912 |

| Macropsalis | forcipata | Sclater | 1866 |

| Thermochalcis | cayennensis | Richmond | 1915 |

| Hydropsalis | furcifer | Wagler | 1832 |

I divide the broad Hydropsalis into 10 genera.

- The Roraiman Nightjar, Hydropsalis whitelyi becomes Tepuiornis whitelyi.

- The Swallow-tailed Nightjar, Hydropsalis segmentata and Lyre-tailed Nightjar, Hydropsalis lyra move to genus Uropsalis.

- Tschudi's Nightjar, Hydropsalis decussata moves to genus Quechuavis.

- The Cayenne Nightjar, Nyctipolus maculosus, Todd's Nightjar, Hydropsalis heterura, and Little Nightjar, Hydropsalis parvula, move to Setopagis.

- The White-winged Nightjar, Hydropsalis candicans, and Sickle-winged Nightjar, Hydropsalis anomala, move to Eleothreptus.

- The Band-winged Nightjar, Hydropsalis longirostris, Rufous-naped Nightjar, Hydropsalis ruficervix, and Tepui Nightjar, Hydropsalis roraimae move to Systellura.

- The Spot-tailed Nightjar, Hydropsalis maculicaudus, moves to Antiurus.

- The Long-trained Nightjar, Hydropsalis forcipata, moves to Macropsalis.

- The White-tailed Nightjar, Hydropsalis cayennensis, moves to Thermochalcis.

- The remaining two Hydropsalis stay in Hydropsalis.

The Cayenne Nightjar, Nyctipolus maculosus, is only known from the type specimen. Cleere (2010) speculates that it is closely related to the Blackish Nightjar, so I have included it in Nyctipolus.

This clade has been augmented by several splits from the Band-winged Nightjar, Systellura longirostris. They include Tschudi's Nightjar, Quechuavis decussata, Tepui Nightjar, Systellura roraimae, both also advocated by Cleere (2010), and Rufous-naped Nightjar, Systellura ruficervix.

Antrostominae: Poorwills Shufeldt, 1889

The second subfamily is Antrostominae, the Poorwills. It consists of Siphonorhis, Nyctiphrynus, Phalaenoptilus, and the possibly unfamiliar genus Antrostomus. This name, due to Bonaparte (1838, type species A. carolinensis), is being applied to one of the New World Caprimulgus nightjars clades. As you can see, it is rather separated from the main group of Caprimulgus.

I have split the Whip-poor-will into Mexican Whip-poor-will, A. arizonae, and Eastern Whip-poor-will, A. vociferus. The Puerto Rican Nightjar (sometimes called Puerto Rican Whip-poor-will) has not been genetically tested. Han's (2006) analysis found the Mexican Whip-poor-will closer to the Dusky Nightjar than to the Eastern Whip-poor-will. However, Sigurðsson (2013) disagreed. The two Whip-poor-will's are vocally distinctive and differ somewhat in plumage, supporting their status as separate species (see also Howell and Webb, 1995; Navarro-Sigüenza and Peterson, 2004).

Based on new information concerning vocalizations, AOS (64th supplement) split the Greater Antillean Nightjar, Antrostomus cubanensis, into Cuban Nightjar, Antrostomus cubanensis and Hispaniolan Nightjar, Antrostomus ekmani.

Chordeilinae: Nighthawks Cassin, 1851

The nighthawk subfamily Chordeilinae is next. There are two genera, Chordeiles and Podager. Rather than follow the AOU's SACC in placing the Least Nighthawk in Chordeiles I now follow the alternative of putting the Least Nighthawk in Podager.

Caprimulginae: Nightjars Vigors, 1825

None of the papers have yet densely sampled the Old World nightjars. I've put the Brown Nightjar, Veles binotatus, in group four on the grounds that is a Old World species sometimes considered part of Caprimulgus. However, others have put it elsewhere (e.g., closer to Chordeiles or Lyncornis). Han (2006) found considerable structure in the remaining Caprimulgus. As a general rule, the Asian species appear to be relatively basal in Caprimulgus. I have rearranged Caprimulgus based on a partial phylogeny and geographic considerations. It's premature to divide these into genera, and I've submerged the genus Macrodipteryx into Caprimulgus.

Schweizer et al. (2020) showed that Vaurie's Nightjar, Caprimulgus centralasicus, is not a separate species. Rather, it is a form of the European Nightjar, Caprimulgus europaeus, likely of subspecies plumipes.

The Gray Nightjar, Caprimulgus indicus, has been split into Jungle Nightjar, Caprimulgus indicus (including kelaarti), Gray Nightjar, Caprimulgus jotaka (including hazarae) and Palau Nightjar, Caprimulgus phalaena (Cleere, 2010).

The Ruwenzori Nightjar, Caprimulgus ruwenzorii, has been merged into the Montane Nightjar, Caprimulgus poliocephalus. See Jackson (2014).

Based on Sangster et al. (2021c), both Franklin's Nightjar, Caprimulgus monticolus (including amoyensis and stictomus) and Chirruping Nightjar, Caprimulgus griseatus (including mindanensis), are split from Savanna Nightjar, Caprimulgus affinis (including propinquus and timorensis).

The Nechisar Nightjar, Caprimulgus solala, has been removed from the TiF list. Shannon, van Grouw, and Collinson, (2025) extracted DNA from the only specimen, a left wing. They found that it was a hybrid. More precisely, its mother was a Standard-winged Nightjar, Caprimulgus longipennis. The identity of the father was not. Its father's identity remains unknown. We do it is one of the nightjars that have not yet been sequenced. However, on morphological grounds, the father is believed to have been a Freckled Nightjar, Caprimulgus tristigma.

Caprimulgidae -- Species List

Nyctidrominae: Neotropical Nightjars

- Band-tailed Nighthawk, Nyctiprogne leucopyga

- Bahian Nighthawk / Plain-tailed Nighthawk, Nyctiprogne vielliardi

- Short-tailed Nighthawk, Lurocalis semitorquatus

- Rufous-bellied Nighthawk, Lurocalis rufiventris

- Common Pauraque / Pauraque, Nyctidromus albicollis

- Scrub Nightjar / Anthony's Nightjar, Nyctidromus anthonyi

- Blackish Nightjar, Nyctipolus nigrescens

- Pygmy Nightjar, Nyctipolus hirundinaceus

- Roraiman Nightjar, Tepuiornis whitelyi

- Swallow-tailed Nightjar, Uropsalis segmentata

- Lyre-tailed Nightjar, Uropsalis lyra

- Tschudi's Nightjar, Quechuavis decussata

- Cayenne Nightjar, Setopagis maculosa

- Todd's Nightjar, Setopagis heterura

- Little Nightjar, Setopagis parvula

- White-winged Nightjar, Eleothreptus candicans

- Sickle-winged Nightjar, Eleothreptus anomala

- Band-winged Nightjar, Systellura longirostris

- Rufous-naped Nightjar, Systellura ruficervix

- Tepui Nightjar, Systellura roraimae

- Spot-tailed Nightjar, Antiurus maculicaudus

- Long-trained Nightjar, Macropsalis forcipata

- White-tailed Nightjar, Thermochalcis cayennensis

- Ladder-tailed Nightjar, Hydropsalis climacocerca

- Scissor-tailed Nightjar, Hydropsalis torquata

Antrostominae: Poorwills

- †Jamaican Pauraque / Jamaican Poorwill, Siphonorhis americana

- Least Pauraque / Least Poorwill, Siphonorhis brewsteri

- Choco Poorwill, Nyctiphrynus rosenbergi

- Eared Poorwill, Nyctiphrynus mcleodii

- Yucatan Poorwill, Nyctiphrynus yucatanicus

- Ocellated Poorwill, Nyctiphrynus ocellatus

- Common Poorwill, Phalaenoptilus nuttallii

- Buff-collared Nightjar, Antrostomus ridgwayi

- Dusky Nightjar, Antrostomus saturatus

- Mexican Whip-poor-will, Antrostomus arizonae

- Eastern Whip-poor-will, Antrostomus vociferus

- Puerto Rican Nightjar, Antrostomus noctitherus

- Tawny-collared Nightjar, Antrostomus salvini

- Yucatan Nightjar, Antrostomus badius

- Silky-tailed Nightjar, Antrostomus sericocaudatus

- Rufous Nightjar, Antrostomus rufus

- Chuck-will's-widow, Antrostomus carolinensis

- Cuban Nightjar, Antrostomus cubanensis

- Hispaniolan Nightjar, Antrostomus ekmani

Chordeilinae: Nighthawks

- Nacunda Nighthawk, Podager nacunda

- Least Nighthawk, Podager pusillus

- Common Nighthawk, Chordeiles minor

- Antillean Nighthawk, Chordeiles gundlachii

- Lesser Nighthawk, Chordeiles acutipennis

- Sand-colored Nighthawk, Chordeiles rupestris

Caprimulginae: Nightjars

- Brown Nightjar, Veles binotatus

- Jungle Nightjar, Caprimulgus indicus

- Gray Nightjar, Caprimulgus jotaka

- Salvadori's Nightjar, Caprimulgus pulchellus

- Jerdon's Nightjar, Caprimulgus atripennis

- Large-tailed Nightjar, Caprimulgus macrurus

- Andaman Nightjar, Caprimulgus andamanicus

- Sulawesi Nightjar, Caprimulgus celebensis

- Philippine Nightjar, Caprimulgus manillensis

- Mees's Nightjar, Caprimulgus meesi

- Bonaparte's Nightjar, Caprimulgus concretus

- Palau Nightjar, Caprimulgus phalaena

- Prigogine's Nightjar, Caprimulgus prigoginei

- Indian Nightjar, Caprimulgus asiaticus

- Madagascan Nightjar, Caprimulgus madagascariensis

- Bates's Nightjar, Caprimulgus batesi

- Standard-winged Nightjar, Caprimulgus longipennis

- Pennant-winged Nightjar, Caprimulgus vexillarius

- Plain Nightjar, Caprimulgus inornatus

- Star-spotted Nightjar, Caprimulgus stellatus

- Swamp Nightjar, Caprimulgus natalensis

- Red-necked Nightjar, Caprimulgus ruficollis

- European Nightjar, Caprimulgus europaeus

- Rufous-cheeked Nightjar, Caprimulgus rufigena

- Sombre Nightjar, Caprimulgus fraenatus

- Long-tailed Nightjar, Caprimulgus climacurus

- Slender-tailed Nightjar, Caprimulgus clarus

- Square-tailed Nightjar, Caprimulgus fossii

- Donaldson Smith's Nightjar, Caprimulgus donaldsoni

- Black-shouldered Nightjar, Caprimulgus nigriscapularis

- Montane Nightjar, Caprimulgus poliocephalus

- Fiery-necked Nightjar, Caprimulgus pectoralis

- Franklin's Nightjar, Caprimulgus monticolus

- Savanna Nightjar, Caprimulgus affinis

- Chirruping Nightjar, Caprimulgus griseatus

- Freckled Nightjar, Caprimulgus tristigma

- Nubian Nightjar, Caprimulgus nubicus

- Golden Nightjar, Caprimulgus eximius

- Egyptian Nightjar, Caprimulgus aegyptius

- Sykes's Nightjar, Caprimulgus mahrattensis

STEATORNITHIFORMES Sharpe 1891

The results of both Hackett et al. (2008) and Braun and Huddleston (2009) suggest the oilbirds and potoos are sisters, which makes sense geographically. Note however, that oilbirds were once more widely distributed. An oilbird fossil is known from Wyoming (Olson, 1987).

Steatornithidae: Oilbird Bonaparte, 1842

1 genus, 1 species HBW-5

- Oilbird, Steatornis caripensis

NYCTIBIIFORMES Informal

The TiF list seems to have been the first to recognize the Nyctibiiformes at an ordinal level.

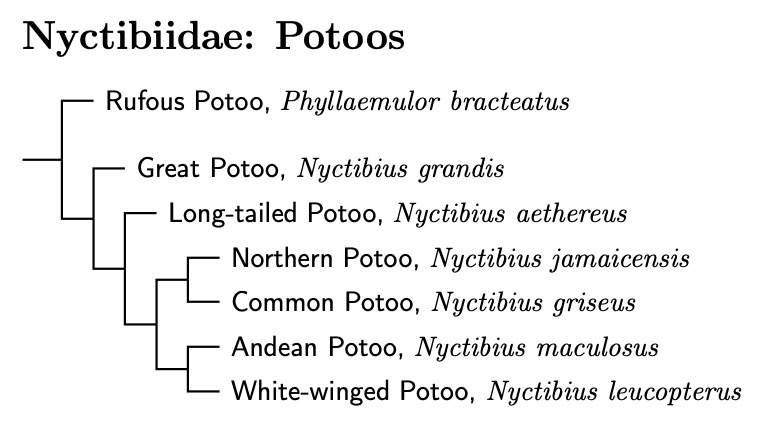

Nyctibiidae: Potoos Chenu & des Murs, 1851

The arrangement of the potoos is based on Braun and Huddleston (2009) and White et al. (2017). There was some uncertainty about the topology found by Braun and Huddleston. This has been resolved by White et al.

|

The Rufous Potoo is rather divergent from the other potoos. As a result it gets its own new genus, Phyllaemulor. The genus was established by Costa et al. (2018).

2 genera, 7 species HBW-5

- Rufous Potoo, Phyllaemulor bracteatus

- Great Potoo, Nyctibius grandis

- Long-tailed Potoo, Nyctibius aethereus

- Northern Potoo, Nyctibius jamaicensis

- Common Potoo, Nyctibius griseus

- Andean Potoo, Nyctibius maculosus

- White-winged Potoo, Nyctibius leucopterus

PODARGIFORMES Sharpe 1891

The Frogmouths are sometimes divided into two families, Podargidae and Batrachostomidae. Molecular evidence indicates they are each other's closest relatives, and I think that is best indicated by placing them in a single family. One new species, the Solomon Islands Frogmouth, was recently discovered (Cleere et al., 2007). It seems to be closer to Podargus than to Batrachostomus.

Following Cleere (2010), Blyth's Frogmouth, Batrachostomus affinis and Palawan Frogmouth, Batrachostomus chaseni) are separated from Javan Frogmouth, Batrachostomus javensis, based on differences in vocalizations. Although Cleere separates it as a separate species, there seems to be some question concerning the vocalizations of the race continentalis (see Marshall, 1978). Until that is clarified, preferably in a journal article, I continue to include it as a subspecies of Blyth's Frogmouth, Batrachostomus affinis.

I had previously split the Bornean Frogmouth, Batrachostomus mixtus, from the Short-tailed Frogmouth (B. poliolophus + mixtus) I have now changed the English name of Batrachostomus poliolophus, from Short-tailed Frogmouth to Sumatran Frogmouth to match.

Although the extant frogmouths are restricted to the Oriental and Australasian regions, they were not always so. Frogmouth fossils have been found in both Europe and the United States (Nesbitt et al., 2011). The American fossils (Fluvioviridavis) are from the Fossil Butte Member of the Green River Formation, and date to approximately 52 million years ago (Grande, 2013). This age underscores the fact that the various orders in the Strisores represent deep divisions in the avian tree.

Nesbitt et al. (2011) also note: “Intriguingly, FBM avian taxa evaluated phylogenetically to date have overwhelmingly been placed along the stem lineages of extant avian subclades comprising traditional `orders' or `families'.”

Podargidae: Frogmouths G.R. Gray, 1847

3 genera, 16 species HBW-5

- Solomons Frogmouth, Rigidipenna inexpectata

- Marbled Frogmouth, Podargus ocellatus

- Papuan Frogmouth, Podargus papuensis

- Tawny Frogmouth, Podargus strigoides

- Large Frogmouth, Batrachostomus auritus

- Dulit Frogmouth, Batrachostomus harterti

- Philippine Frogmouth, Batrachostomus septimus

- Gould's Frogmouth, Batrachostomus stellatus

- Sri Lanka Frogmouth, Batrachostomus moniliger

- Hodgson's Frogmouth, Batrachostomus hodgsoni

- Sumatran Frogmouth, Batrachostomus poliolophus

- Bornean Frogmouth, Batrachostomus mixtus

- Javan Frogmouth, Batrachostomus javensis

- Blyth's Frogmouth, Batrachostomus affinis

- Palawan Frogmouth, Batrachostomus chaseni

- Sunda Frogmouth, Batrachostomus cornutus

AEGOTHELIFORMES Simonetta, 1967

The owlet-nightjars branched off from other taxa in Strisores about 55 mya. Prum et al. (2015) estimated the event at 56 mya, while Kuhl et al. (2021) preferred 52.6 mya. Some sources prefer to include owlet-nightjars in Apodiformes, but given their age, I now rank them as an order, as has the IOC list.

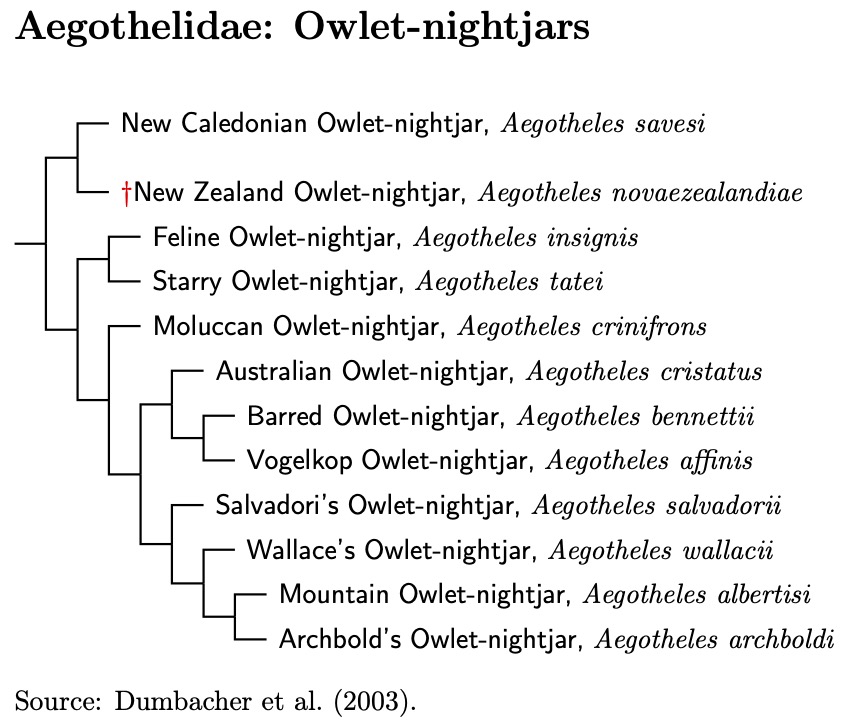

Aegothelidae: Owlet-nightjars Bonaparte, 1853

1 genus, 12 species HBW-5

The owlet-nightjars seem to be more closely related to the traditional Apodiformes (swifts and hummingbirds) than they are to the nightjars. This is not only supported by molecular evidence, but also by morphology (see Mayr, 2002; 2008a). The arrangement of species follows Dumbacher et al. (2003), which also provided evidence that neither A. archboldi nor A. salvadorii are subspecies of A. albertisi, contra IOC (true as of 14.1). The IOC list also includes A. terborghi as a subspecies of A. bennettii, when Dumbacher et al. found it grouped with A. affinis.

There is some confusion concerning English names. Cleere (2010) uses the name Salvadori's Owlet-nightjar to refer to affinis, not salvadorii while the IOC used it to refer to salvadorii, calling affinis the Vogelkop Owlet-nightjar. It might be less confusing to use another name for salvadorii, but I don't know of any in current use that help. The term Mountain Owlet-nightjar is also a problem. H&M-4 (Dickinson and Remsen, 2013), which recognizes the same species as the TiF list, uses Mountain Owlet-nightjar for salvadorii and Arfak Owlet-nightjar for albertisi, further adding to the confusion.

I've included the extinct New Zealand Owlet-nightjar, Aegotheles novaezealandiae. See Holdaway et al. (2002) for more about this species. Dumbacher et al. (2003) were able to obtain DNA, hence the position on the tree.

- New Caledonian Owlet-nightjar, Aegotheles savesi

- †New Zealand Owlet-nightjar, Aegotheles novaezealandiae

- Feline Owlet-nightjar, Aegotheles insignis

- Starry Owlet-nightjar, Aegotheles tatei

- Moluccan Owlet-nightjar, Aegotheles crinifrons

- Australian Owlet-nightjar, Aegotheles cristatus

- Barred Owlet-nightjar, Aegotheles bennettii

- Vogelkop Owlet-nightjar, Aegotheles affinis

- Wallace's Owlet-nightjar, Aegotheles wallacii

- Salvadori's Owlet-nightjar, Aegotheles salvadorii

- Mountain Owlet-nightjar, Aegotheles albertisi

- Archbold's Owlet-nightjar, Aegotheles archboldi